The Book of Colossians

About

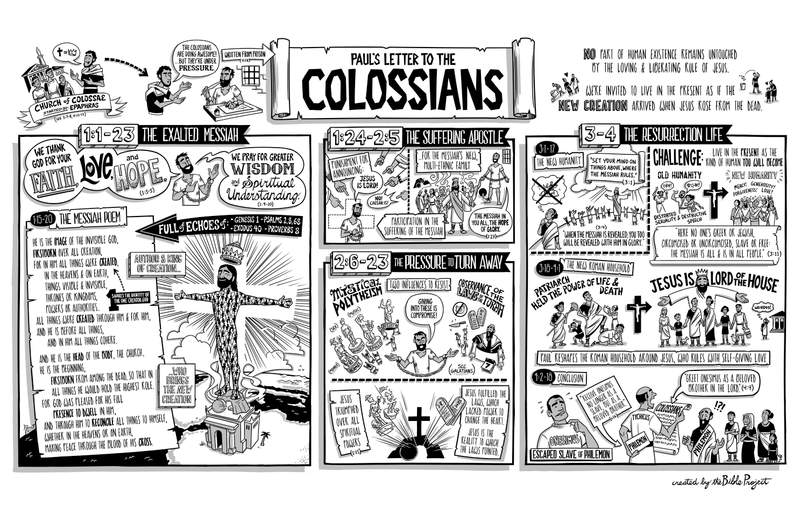

This letter was written during one of Paul’s many imprisonments for announcing Jesus as King. Unlike his other letters, this is addressed to a group of people that he had never met and a community that he didn’t start. The church in Colossae was started by a coworker of Paul’s named Epaphras, who was from Colossae (Col. 1:7-8; 4:12-13). Epaphras had recently visited Paul in prison and updated him on how well the Colossians were doing overall. However, Epaphras had also mentioned some of the cultural pressures that were tempting them to turn away from Jesus. Paul wrote this letter to encourage the Colossians, address the issues Epaphras had raised, and challenge them to a greater devotion to Jesus.

The letter’s design and flow of thought are fairly easy to follow. The opening movement focuses on Jesus as the exalted Messiah, followed by Paul’s description of his suffering in prison for the Messiah. Then, Paul addresses the pressures tempting them to turn away from Jesus. In chapters 3-4, Paul explores the new way of life that Jesus’ resurrection has opened up for them.

Who Wrote the Book of Colossians?

Context

Key Themes

- Jesus as King over all creation

- Liberation through Jesus

- Freedom in the Messiah

Structure

Colossians 1:1-23: Jesus As King Over All Creation

The letter opens with two prayers. Paul first thanks God for what he learned from Epaphras, that the Colossians have been totally faithful to Jesus and showing love for God and their neighbors. He moves on to pray that they will grow in their wisdom and understanding about Jesus. Paul has placed a poem here to help the Colossians and us do exactly that (Col. 1:15-20). It’s the centerpiece of chapter 1, and it’s all about the crucified and exalted Messiah.

This poem has two parallel stanzas crammed with language and imagery from the books of Genesis, Exodus, the Psalms, and Proverbs. The first stanza explores how Jesus is the true image of God. In him, the full character and purpose of God is embodied in a human. Jesus is the firstborn, an Old Testament phrase about Jesus’ royal status, over all creation. In this, he shares the very identity of the one true Creator God. Through him, all reality, all powers and authorities, both spiritual and human, were created.

It’s in Jesus the Messiah that we discover the author and King of creation, as well as the one who will bring about the new creation. He’s the head of a new body, which refers to Jesus’ people, who are the new humanity of which his resurrection existence is a prototype. God’s glorious temple presence dwells in Jesus. And God has reconciled himself to humanity, all spiritual powers, and all creation through Jesus’ death and resurrection. It’s a remarkable poem, and Paul will keep referring back to it as he continues with the letter.

Colossians 1:24-2:5: Paul’s Suffering

Paul then shows how the truth of this poem transforms his own experience of suffering in prison (Col. 1:24-2:5). While he’s being punished for announcing Jesus as the risen Lord and King to the Greek and Roman world, his suffering is not a defeat. It’s actually Paul’s way of participating in Jesus’ own suffering, which was also done as an act of love. Paul’s hardships are a cause for joy, as he has been imprisoned for spreading the surprising news about Israel’s resurrected Messiah. Just as the divine glory dwells in Jesus, so Jesus dwells in and among his international family. In Paul’s words, “the Messiah is in you all, the hope of glory” (Col. 1:27).

Colossians 2:6-23: Cultural Pressures

Paul then addresses the cultural pressures that are tempting the Colossians to turn away from Jesus (Col. 2:6-23).They were being confronted by a combination of mystical polytheism and pressure to observe the laws of the Torah. All of these new Christians had grown up worshiping the various Greek and Roman gods who governed different arenas of everyday life. And some of the Colossian Christians considered Jesus as one more deity that they could worship alongside the others. From a different cultural group, the Jewish Christian were pressuring these non-Jews to “complete” their commitment to the Messiah by following all the laws found in the Torah. Paul specifically mentions the pressures of eating a kosher diet, observing sacred days, and circumcision (Galatians).

For Paul, to give into these temptations is an unacceptable compromise and a failure to grasp who Jesus is and what he accomplished on their behalf. The Colossians used to live in fear of spiritual powers and “elemental spirits,” as Paul calls them (Col. 2:8; Col. 2:20). But Jesus has triumphed over these powers through his death and resurrection, freeing the Colossians from any former obligation to these powers. In the same way, Jesus has fulfilled all the laws of the Torah, which never had the power to transform the selfish human heart. What Jesus did through his life, death, and resurrection lacks nothing and doesn’t need to be supplemented by following the old laws. After all, Jesus is the reality to which the Torah was pointing all along.

Colossians 3-4: Examples of Jesus’ Self-Giving Love

Rather than trying to live under the laws of the Torah, Christians have the power of Jesus’ resurrection to change their hearts, minds, and way of life. Following Jesus means joining the new humanity and joining their lives to the risen Jesus. This is why Paul challenges the Colossians to “set their minds on things above, where the Messiah is seated” and where he rules at God’s right hand (Col. 3:1). Paul doesn’t mean for them to think about leaving Earth to go to Heaven. Rather, the heavens are the transcendent place from which Jesus rules over creation. From there, he will one day return to Earth to transform all things. Or, as Paul says, “When the Messiah, who is your life, is revealed, you too will be revealed with him in glory” (Col. 3:4).

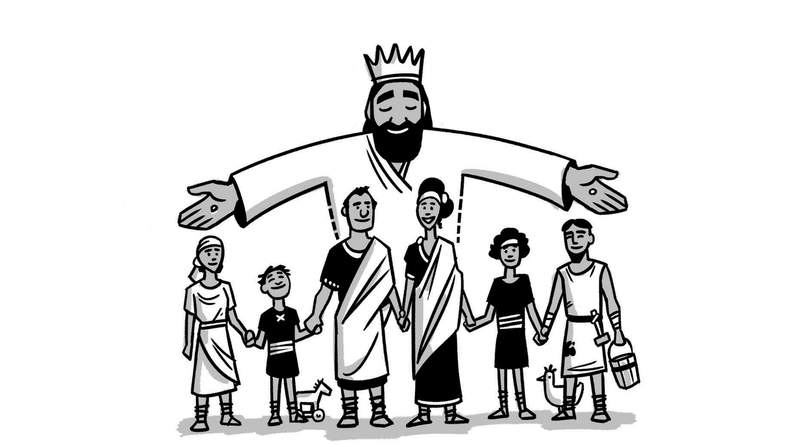

Paul challenges them to live in the present as the new kinds of humans that they will one day become. Paul describes their old humanity, which was characterized by distorted sexuality and destructive speech. For Christians, that old humanity died along with Jesus and is replaced with his new humanity, characterized by mercy, generosity, forgiveness, and love. This new humanity transcends the ethnic and social boundary lines of the world in order to create, in Paul’s words, a people in which “no one is Greek or Jewish, circumcised or uncircumcised, slave or free. But the Messiah is all, and is in all people” (Col. 3:11).

Paul next offers a practical example of this concept, showing the Colossians what this new humanity might look like in a first-century Roman family. The Roman household was a highly authoritarian institution, in which the patriarch held the power of life and death over his wife, children, and slaves. This is not so in a Christian household because the risen Jesus is the true Lord, where the wife allows her husband to be responsible for her, and the husband is subject to Jesus by loving his wife and placing her well-being above his own.

In a home where Jesus is Lord, children are not objects but called to maturity and respect. Parents are to raise their children with patient understanding. And Christians who are enslaved are also to honor their human masters precisely because they’re not the real master—Jesus is! Christians who have enslaved other people are to understand that these people are not their property but are fellow members of Jesus’ body. They are to be honored and embraced in love.

Paul is walking a fine line here. He takes the most basic Roman institution and reshapes it around Jesus, who rules with self-giving love. While he doesn’t abolish the household structure outright, the exalted Messiah demands that it be transformed almost beyond the point of recognition for any Roman living in Colossae.

You can see this most clearly in the letter’s conclusion (Col. 4:2-18). After a request for prayer, Paul applies these instructions about Christian enslaved people and masters to the church at Colossae. We discover that Tychicus is the one carrying and reading this letter to the Colossians and that he’s accompanied by Onesimus, a person formerly enslaved to a Colossian Christian named Philemon. We also discover, from another letter of Paul’s addressed to Philemon, that Onesimus had escaped from his master—a crime that was worthy of imprisonment. In the face of all this relational tension, Paul asks the church to greet Onesimus “as a faithful and beloved brother in the Lord” (Col. 4:9). In the letter to Philemon, Paul is even more clear. He says that Onesimus should be received “no longer as a slave, but as a brother” (Phil. v. 16).

In this letter, Paul invites us to see that no part of human existence remains untouched by the loving, liberating rule of the risen Jesus. Our suffering, temptation to compromise, and moral character, and the power dynamics inside our homes must be reexamined and transformed. We are invited to live in the present as if the new creation really arrived when Jesus rose from the dead.