The Book of Ecclesiastes

About

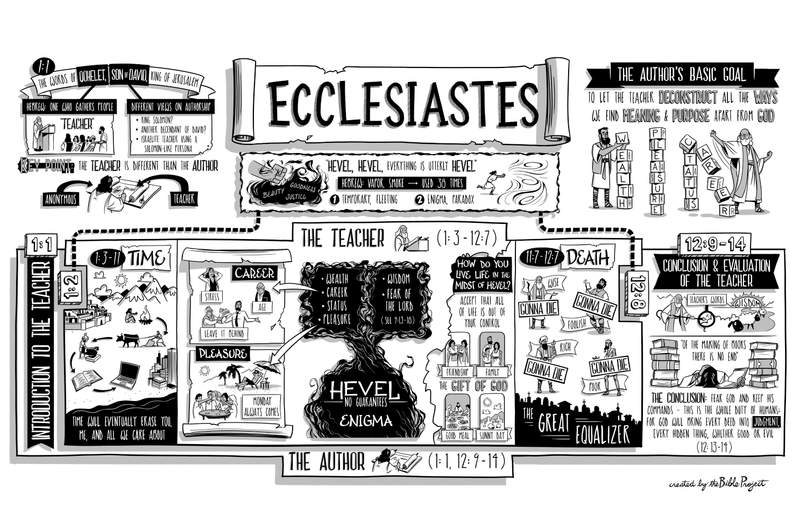

This unique book within the Bible’s wisdom literature opens with this line: “The words of Qohelet, son of David, king in Jerusalem.” The Hebrew word qohelet means “one who gathers people together.” In this case, the gathering is to listen and learn, so the word is often translated as “teacher.” This person is said to be a son or descendant of King David, but there are differing opinions on who this figure really is. Many have thought that it refers to King Solomon. Others look at later kings from David’s line, and still others think that it’s a later Israelite teacher who’s adopted a “Solomon-like persona” as a teaching aid.

Whichever of these views is correct, the key thing to recognize is that the teacher is a character in the book and is different from the author of the book, who remains anonymous. While we do hear the voice of the teacher for most of the book, it’s actually a different voice, that of the author, who first introduces us to the teacher and who concludes the book by summarizing and evaluating all that the teacher has said. This is someone who not only wants us to hear everything that the teacher has to say, but also wants to help us process it and form our own conclusion.

Who Wrote the Book of Ecclesiastes?

Context

Key Themes

- Lack of meaning and purpose in life apart from God

- The limitations of wisdom

- Enjoying God’s good gifts

- Fear of God

Structure

The Message of the Teacher in Ecclesiastes

So what exactly does the teacher have to say? The author summarizes the teacher’s basic message at the beginning (Ec. 1:2) and the end (Ec. 12:8): “Hevel, hevel, everything is utterly hevel.” Most English Bibles translate this word hevel as “meaningless,” but that doesn’t quite capture the entire idea. In Hebrew, hevel literally refers to “vapor” or “smoke.” The teacher uses this word 38 times throughout the book of Ecclesiastes as a metaphor to describe how life is temporary and fleeting, like a wisp of smoke, but also how life is an enigma or paradox. Smoke appears solid, but when you try to grab it, it’s like nothing is there.

Here’s what the teacher is getting at. There’s so much goodness and beauty in the world, but just when you are enjoying it, tragedy strikes and it all seems to blow away. Most people believe in right and wrong and have a sense of justice, so why do bad things happen to good people all the time, despite our best intentions? Life is constantly unpredictable and unstable or, in the teacher’s description, like “chasing the wind.”

“All is hevel.” This is the teacher’s basic motto, and it is a total downer. Why is he saying all of this? The author’s basic goal is to target all of the ways we try to build meaning and purpose in life apart from God and then let the teacher deconstruct them. The author thinks that people spend most of their time investing energy and emotion in things that ultimately have no lasting meaning or significance. And so he allows the teacher to give us a reality check.

Ecclesiastes 1:3-12:7: Life Apart from God

You can see this most clearly in the opening and closing poems, which focus on time (Ec. 1:3-11) and death (Ec. 11:7-12:7). The teacher says that if your whole focus is about working and achieving in order to bring meaning to your life, you need to stop and consider the march of time. For all the human effort that takes place in the world, nothing really changes. Sure, we develop technology and entire nations rise and fall, but go climb a mountain and see if it cares. That thing was there long before any of us, and it will remain there long after we’re gone. A hundred years from now, no one will remember you or me or anything that we did, but that mountain will still be there, and the ocean will still be breaking on the beach, and the sun will still rise and set. Time will eventually erase you, me, and all we care about.

If that’s not disheartening enough, the teacher also can’t stop talking about death throughout the entire book, especially in the poem near the end (Ec. 11:7-12:7). Death is the great equalizer. It renders meaningless most of our daily activities. No matter who you are, or what you’ve done, good or bad, everyone eventually dies. Death devours the wise and the foolish, the rich and poor. It’s inescapable.

With these two ideas in hand, the teacher considers all the activities and false hopes in which we invest our lives in order to find meaning and significance: wealth, career, social status, or pleasure. However important these may seem, the march of time and our impending death reduce all of it to hevel. You think working hard in your career makes life worth it? Think of all the stress and the toll it takes on you, the anxiety, the sleepless nights. You’re probably going to be too old to enjoy the payoff by the time you earn it, and by then you have to pass it off to others who may or may not even care about your accomplishments. What about pleasure? Do you think that’s what life is all about? Go for it, live for your vacations and the weekend parties. Monday always comes.

What does the teacher advocate then? Should we all become pure hedonists or relativists? No, because that’s hevel too. The teacher acknowledges the core ideas from Proverbs—living by wisdom and the fear of the Lord has real advantages. On the whole, life will probably go better for you if you live that way (Ec. 7:11-12, 9:13-18). The problem is that living by wisdom and the fear of God are also hevel because they can’t guarantee a good life. Good people can still die tragically while horrible people can still live long and prosper. There are just too many exceptions, and so even wisdom is hevel. Once again, this doesn’t mean that it’s entirely meaningless, but it is an enigma because it doesn’t always work the way you think it should.

So what’s the way forward in the midst of all this hevel? Paradoxically, the teacher discovers that the key to truly enjoying life is accepting hevel, acknowledging that everything in your life is totally out of your control. About six different times, at the bleakest moments in his dialogue, the teacher suddenly talks about “the gift of God,” which is the enjoyment of the simple, good things in life such as friendship, family, a good meal, or a sunny day.

You and I can’t control the most important things in our lives. Nothing is guaranteed, and, strangely, that’s the beauty of it. When I adopt a posture of complete trust in God, it frees me to simply enjoy life as I actually experience it and not as I think it ought to be. In the end, even my expectations about life, my hopes and dreams, are all “hevel, hevel. Everything under the sun is hevel.”

Ecclesiastes 12:9-14: The Author’s Wise Conclusion

The teacher’s words come to an end, and the author takes over, bringing the book to a close. He says that it is very important to hear what the teacher has to say. He likens the teacher’s words to a shepherd’s staff with a goad, a pointy end that will hurt when it pokes you. But that pain can ultimately steer you in the right direction towards greater wisdom.

The author warns us not to take the teacher’s words too far. You can spend your entire life buried in books trying to answer the existential puzzles of human life. Don’t exhaust yourself, he says. You’ll never get there. Instead, the author offers his own conclusion that we should “fear God and keep his commands; this is the whole duty of humans. For God will bring every deed into judgment, every hidden thing, whether good or evil” (Ec. 12:13-14).

It’s good to let the teacher challenge our false hopes and remind us that time and death make most of life totally out of our control. What gives life true meaning is the hope for God’s judgment, that God will one day clear away all the hevel and bring true justice to our world. It’s this hope that should fuel a life of honesty and integrity before God, even if we remain puzzled by life’s mysteries. And strangely, it’s the puzzle that can lead us to true peace.

That’s the surprising wisdom of the book of Ecclesiastes.