The Book of Jonah

About

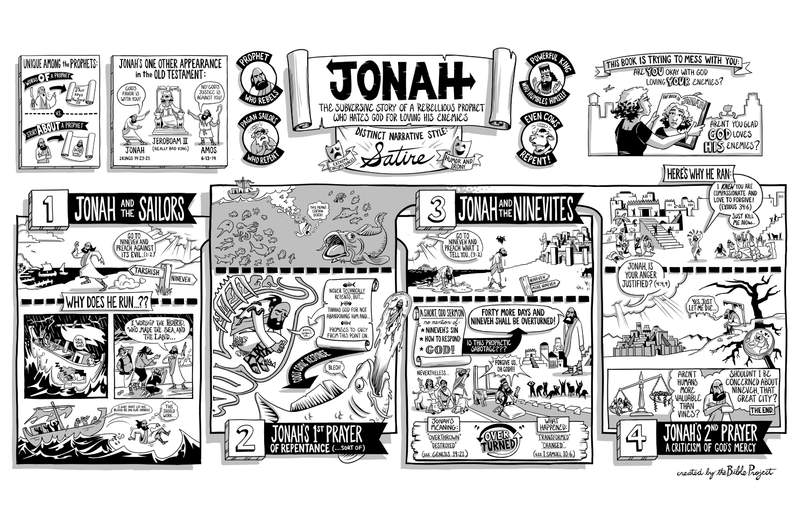

One important aspect of the ancient TaNaK order of the Hebrew Bible is that the 12 prophetic works of Hosea through Malachi, sometimes referred to as the Minor Prophets, were designed as a single book called The Twelve. Jonah is the fifth book of The Twelve.

Jonah is unique among the books of the prophets, which are typically collections of God’s words spoken through a prophet. This book doesn’t really focus on the words of a prophet; rather, it’s a subversive story about a prophet who resents his God for loving his enemies.

The prophet Jonah appears only one other time in the Old Testament, during the reign of one of Israel’s worst kings, Jeroboam II. Jonah prophesied in his favor, promising that he would win a battle and regain territory on Israel’s northern border (2 Kgs. 14:23-25). Now, it’s important to know that the prophet Amos confronted Jeroboam II and that, through him, God specifically reversed Jonah’s prophecy (Amos 6:13-14). Amos promised that Jeroboam II would lose those same territories because of his sin. So before Jonah’s story even begins, we’re already a bit suspicious of this character.

The book of Jonah is beautifully designed and is full of exquisite literary pairing and symmetry. Chapters 1 and 3 tell the story of Jonah’s encounters with non-Israelites, first with some sailors, and later on with his hated enemies the Ninevites. Each story offers a comic contrast between Jonah’s selfishness and their humility and repentance. Chapters 2 and 4 contain prayers of Jonah, one a prayer of repentance, sort of, and the other a prayer in which Jonah calls God out for being too merciful and kind.

This careful design is matched by a very distinct style of narrative. The story is full of stereotyped characters who, ironically, do the exact opposite of what you would expect. The prophet, a man of God, rebels against and can’t stand his own God. The sailors, who are supposed to be immoral pagans, have soft repentant hearts and turn to God in humility. The king of the most powerful murderous empire on Earth humbles himself because of Jonah’s five-word sermon—even his cows join in the repentance. This kind of story fits in with what we would today call satire—stories about well-known figures in extreme circumstances, using humor and irony to critique their stupidity and character flaws.

Who Wrote the Book of Jonah?

Context

Key Themes

- God’s love and compassion for his enemies

- The disobedience of Jonah and Israel

- Repentance and forgiveness

Jonah 1: Jonah Runs From God

The story opens with God addressing Jonah, commissioning him to go preach against the evil and injustice in Nineveh, the capital city of the Assyrian empire and Israel’s bitter enemy. Instead of going east to Nineveh, Jonah runs in the opposite direction and finds a ship going as far west as one could possibly go, to Tarshish. The big question is, of course, why? Why does he run? Is he afraid? Does he just hate Ninevites? We’re not told yet.

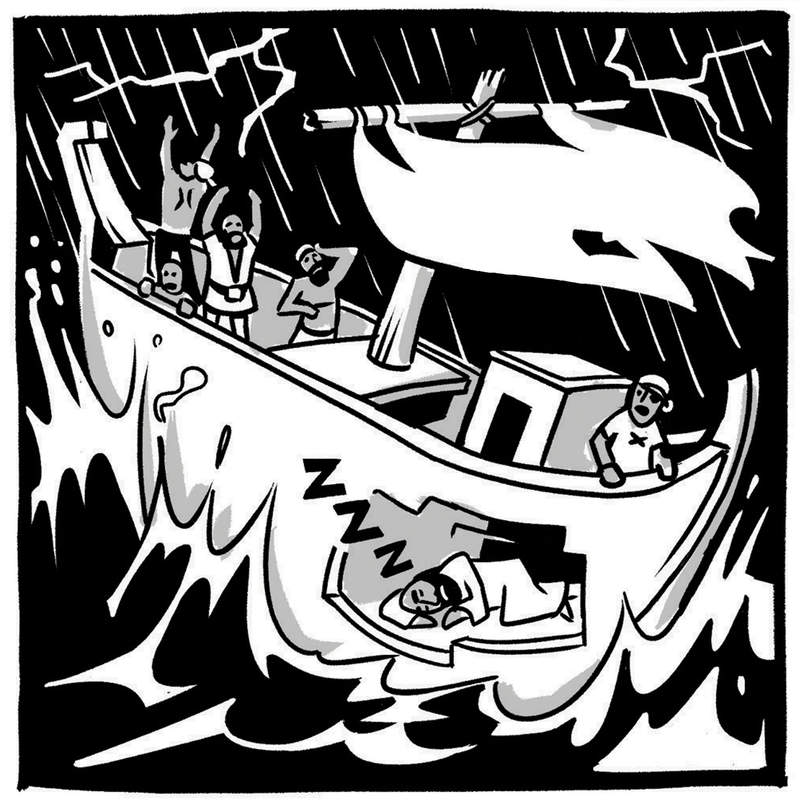

So the man of God tries to run from his God. He boards a ship full of pagan sailors and promptly goes below deck and falls asleep. God has to send a huge storm just to wake up his own prophet, while ironically the sailors are wide awake and see exactly what’s happening. They discern that a divine power is at work, so they throw dice and discover that it’s Jonah’s sin that’s causing the problem. When asked to explain himself, Jonah spouts off a bunch of religious mumbo-jumbo: “I’m a Hebrew, and I worship the LORD, who made the sea and the land” (Jon. 1:9). What a joke! He’s obviously right in saying that God made the sea and dry land, but then he’s dumb enough to run from that very same God by getting on a boat?! When the sailors ask Jonah what to do, he says that they should just kill him by throwing him overboard. This seems noble at first, until you realize that this could be his most selfish move yet. What better way to avoid going to Nineveh?

He puts his blood on the innocent sailors’ hands by forcing them to kill him. The sailors remain reluctant and actually repent to God as they toss the prophet over. The storm subsides and they come to fear the God of Israel and, unlike Jonah, actually worship him.

Jonah 2: Jonah’s Prayer Inside the Fish

God foils Jonah’s plans to escape Nineveh by providing a strange, watery tomb for him—the stomach of a large fish. Under normal circumstances, this would mean certain death, but in this story, everything is upside-down. Jonah’s submarine death becomes his passage back to life. Cramped within the stomach of the beast, Jonah utters a prayer. He never technically says that he’s sorry, but he does thank God for not abandoning him and promises that he will obey his God from this point on, no matter what. God’s response is comical—the fish vomits Jonah out back onto dry land.

Jonah 3: Jonah’s Sermon and Nineveh’s Repentance

Once again, God commissions Jonah to go and preach in Nineveh, and this time he complies. We’re told that Nineveh was a gigantic city that took days to walk through. Jonah only gets one day in and spreads this message, “Forty more days and Nineveh will be overturned.” His sermon is very short—a mere five words in the original Hebrew—and it’s also a bit odd. Look at what’s missing: There’s no mention of what the Ninevites have done wrong or what they should do to respond, no mention of who might overturn them, and, most noticeably, there’s no mention of God. What’s going on here? Has Jonah intentionally given the bare minimum of information? Is he trying to sabotage his own message? It’s almost like he’s trying to ensure their destruction, as there’s just no effort on his part.

Whatever his hidden motives are, the plan doesn’t work. No sooner does he utter his five-word sermon than the king of Nineveh and the entire city, including their cows, all repent in sorrow and ashes. For the second time, the “evil pagans” show themselves to be more responsive and humble than God’s own prophet. God forgives the Ninevites and doesn’t bring destruction down on the city.

Now, here’s a brilliant part of this story. The last word of Jonah’s short sermon, “overturned,” means just that, “turned over.” It can refer to a city being overthrown or destroyed, like Sodom was in Genesis 19:21, but it can also be used to mean transformation, something being turned over and changed into its opposite (1 Sam. 10:6). So ironically, Jonah’s words did come true, but not in the way he intended. Nineveh gets turned over as Jonah’s enemies repent and find God’s mercy.

Jonah 4: Jonah Confronts God for Loving His Enemy

The final chapter brings all the pieces together. Jonah is fuming mad and utters his second prayer. He first tells God why he ran away back in chapter 1. It wasn’t because he was afraid but because he knew that God is so kind and merciful. Jonah actually quotes God’s self-description from Exodus 34:6 and throws it back in his face as an insult. He knew that God is compassionate and would find a way to forgive those horrible Ninevites. You can almost hear the disgust in Jonah’s voice before he cuts off the conversation and prays that God would just kill him on the spot. He’d rather die than live with a God who forgives his enemies.

Fortunately for Jonah, God doesn’t comply but simply asks if Jonah’s anger is justified. Jonah ignores the question and goes outside the city to camp on a nearby hill, waiting to see what will happen. Maybe those Ninevites will repent of their repentance and get roasted after all.

What happens next is a little odd. God provides a vine plant to shade Jonah from the sun, which makes him quite happy, but then God sends a tiny worm to eat the plant. Jonah loses his shade and gets really angry again. In the heat of the sun, Jonah asks again that God kill him. And God asks Jonah a second time if his anger is justified. Jonah barks back, “Absolutely, just let me die!” And those are Jonah’s last words in the book.

It’s God who speaks the final words of the book. He says that the whole vine incident was an attempt to get through to Jonah. He got all emotional over this withered vine that he only enjoyed for a day. But God asks, aren’t humans a bit more valuable than vines? Isn’t it okay if God feels the same emotional intensity and concern for the city of Nineveh, full of thousands of people who have lost their way? The book ends right there with God asking Jonah for permission to show mercy to his enemies and their cows.

Jonah’s answer? Well, the story doesn’t say, because that's not really the point. The point is that this book is trying to mess with you—God’s questions are really addressed to you, the reader. Are you okay with the fact that God loves your enemy?

The book of Jonah holds up a mirror to whoever reads it. In Jonah, we see the worst parts of ourselves magnified, which should generate humility and gratitude that God does love his enemies and puts up with the Jonah in all of us. This strange story becomes a message of good news about the wideness of God’s love, which ought to challenge us to the core.