The Book of Jude

About

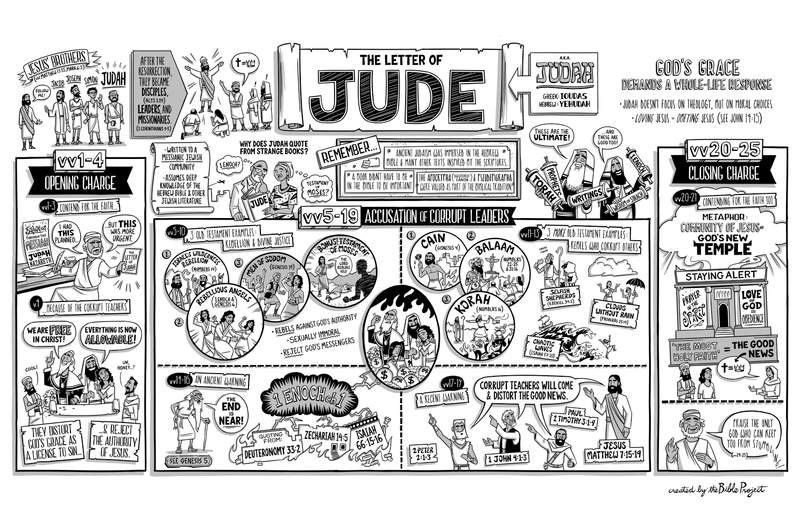

This letter was written by Jude, or more accurately “Judah,” according to the pronunciation of his name in Greek (Loudas) and Hebrew (Yehudah). He was one of Jesus’ four brothers named in the gospel accounts (Matt. 13:55; Mark 6:3). None of them followed Jesus as the Messiah before his death (John 7:5), but they all became his disciples once they saw him risen from the dead (1 Cor. 15:7). All of these brothers became leaders in the first Jewish Christian communities, with Judah acting as a traveling teacher and missionary (1 Cor. 9:5).

All of this gives us a background from which to understand the purpose of this letter. We don’t know what specific community Judah wrote to, but it was very likely made up of mostly messianic Jews. His writing style assumes a deep knowledge of the Old Testament Scriptures as well as other popular Jewish literature.

Judah had become aware of a crisis that was facing this church, which helps us better understand the letter’s design. It begins with an opening charge in Jude 1:1-4, followed by a long warning and accusation in Jude 1:5-19 against corrupt teachers who had been influencing the church. Judah then concludes the letter by completing a charge about what this church should do (Jude 1:20-25).

Who Wrote the Book of Jude?

Context

Key Themes

- God’s justice and judgment

- Jesus as the new temple

- Loving God through obedience

Structure

Jude 1:1-4: Contend for the True Faith

Judah starts by charging the church to contend for the true Christian faith. His plan had been to write a much longer work that explored “our shared salvation” through the Messiah, but that project got delayed when he heard the urgent news about this church. He instead fired off this short but thoughtful letter. In any case, Judah doesn’t begin with how the people are to contend for the faith; rather, he first goes into why they should. Corrupt teachers have infiltrated the community. And it’s not their teaching that Jude targets but their way of life. Their moral compromise is how we can know that they have bad theology.

Jude 1:5-19: Beware of False Teachers

Judah wants this church to know that the appearance of these teachers is not a surprise and he transitions into a longer warning to stay away from them. He offers two sets of three Old Testament examples, the first of which is about rebellious people who received divine justice (Jude vv. 5-10). The Israelites who rebelled against God in the wilderness got what they wanted, and they were barred from entering the promised land and died in the middle of nowhere (Num. 14).

The next story is about angels who are imprisoned for their rebellion until they face God’s final justice. What Judah is referring to here is the interpretation of Genesis 6 that was offered in the popular Jewish work 1 Enoch. In it, the sons of God are interpreted as being angels who go on to rebel against God, have sex with women, and are judged accordingly. Judah’s third example is about the ruin of Sodom and Gomorrah in Genesis 19, in which violent men try to have forced sex with angels. Both of those last stories are about rebellion against God that specifically led to sexual immorality. This is precisely what the corrupt teachers are guilty of doing.

Judah also brings up a bonus example from another popular Jewish text called the Testament of Moses, which, like 1 Enoch, was not a part of the Old Testament Scriptures. It’s a creative retelling of Moses’ final days and words from chapters 30-34 of Deuteronomy. In the story Judah quotes from, Moses has died and the good angel Michael is refuting the devil’s accusations against him, but Michael leaves the final judgment for God alone.

While these stories may seem odd to us, for Jewish people who were raised on this literature, Judah’s warning makes sense. The behavior of the corrupt teachers has ancient roots. Rebellion against God’s authority, sexual immorality, and rejection of God’s angelic messengers is nothing new and should not take Judah’s listeners by surprise.

This all connects to the second trio of examples about rebels who went on to corrupt others. Cain murdered his brother and went on to build a city where violence reigned (Gen. 4). Balaam couldn’t curse Israel, so he lured them into idolatry and sexual misbehavior (Num. 31:16). Korah the Levite led a rebellion against Moses that ended in disaster for many others (Num. 16). Judah concludes this second trio with a barrage of Old Testament images describing the teachers. They’re like the selfish shepherds of Ezekiel 34:2, the clouds with no rain from Proverbs 25:14, or the chaotic waves from Isaiah 57:20. Their self-absorption betrays their claim to follow Jesus, and they bring chaos wherever they go.

Judah concludes his warnings by quoting two other warnings, one ancient in Jude 1:14-16 and one recent in Jude 1:17-19. The first comes from 1 Enoch, which claimed to contain the visions of the ancient figure of the same name (Gen. 5:21-24). What’s fascinating about this is that Judah quotes from the opening section of Enoch, which is itself quoting half a dozen Old Testament texts about the final Day of the Lord (Deut. 33:2; Zech.14:5; Isa. 66:15-16).

Judah then matches Enoch’s ancient warning with a more recent one from the apostles. Peter, John, and Paul all predicted that corrupt teachers would arise and distort the good news, denying Jesus by their actions (1 John 4:1-3; 2 Tim. 3:1-9; 2 Pet. 2:1-3). And they were echoing Jesus’ earlier warning of the same thing (Matt. 7:15-19). With all these examples, hopefully this church wouldn’t need any more convincing that these teachers have to be dealt with.

Jude 1:20-25: How to Contend for the Faith

With that, Judah moves into his closing charge, picking up his opening line about “contending for the faith.” He unpacks how to do this through a set of metaphors. The community of Jesus is God’s new temple, so they are to build their lives on the foundation of “the most holy faith,” referring to the core message of the good news about Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection. On that foundation, the Church is to build itself up through dedication to prayer and by devoting itself to the love of God through obedience. The integrity of this building will be maintained by staying alert for the return of Jesus as well as by helping each other stay faithful. Judah concludes by praising the God who will protect his people and keep them from falling too far from his grace.

This short letter is very powerful, but it is puzzling for many modern readers. Why does Judah quote from texts that were never considered a part of the Scriptures like 1 Enoch or the Testament of Moses? It’s important to remember that the Jewish culture of this time was immersed in religious texts. Jesus, his family, and all of the early Jewish Christians grew up reading the Hebrew Bible along with many other books based on and inspired by the Scriptures.

This is no different than reading popular religious books by authors in our own day. While they’re not a part of the Bible, many other texts offer powerful messages to God’s people. Many Jewish texts from this period, known today as the collections of the Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha, were preserved and read in Jewish and Christian communities and treated with great respect. That doesn’t mean that they were originally designed to be a part of the Hebrew Bible, and virtually no one thought that they were. But because Judah knows his audience, he used these texts to make his point. His readers were familiar with this literature, and it could help him communicate his message.

And his message was that God’s grace through Jesus demands a whole-life response not just intellectual assent. Notice that Judah doesn’t criticize or focus on the corrupt teacher’s theology but on their immoral way of life. Judah is applying what Jesus first told his disciples: “If you really love me, you’ll obey my teachings” (John 14:15). And for Christians of every age, how we live is the most reliable indicator of what we actually believe.