The Book of Judges

About

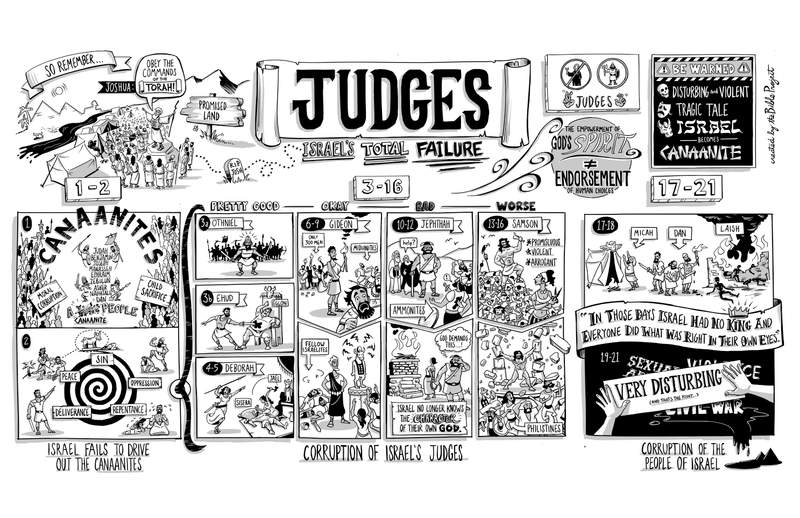

In the previous book, Joshua finally led the tribes of Israel into the promised land, calling on them to be faithful to their covenant with God by obeying the commands of the Torah and being an example to other nations. The book of Judges begins with the death of Joshua and, unfortunately, tells the story of Israel’s total failure.

The book’s name comes from the types of leaders Israel had in this period. Before they had any kings, the tribes of Israel were ruled by judges. Don’t think of a courtroom here, because these were regional, political, and military leaders, more like tribal chieftains. Now, be warned, the book of Judges is disturbing and violent. It tells the tragic tale of Israel’s moral corruption, bad leadership, and how they became no different than the Canaanites themselves.

However, this sad story is also meant to generate hope for the future, which you can see illustrated in the book’s design. There’s a large introduction in chapters 1-2 that sets the stage for Israel’s failure as they don’t drive out the remaining Canaanites like they were told to. The large, main section of the book (Judg. 3-16) has stories of the growing corruption of Israel’s judges. The progression here shows how Israel’s leaders went from pretty good to okay to bad to worse. The concluding section (Judg. 17-21) is really disturbing and shows the corruption of the people of Israel as a whole. Let’s dive in and explore each part a bit more.

Who Wrote the Book of Judges?

Context

Key Themes

- God’s grace to preserve people through their rejection of his instruction

- Israel’s desperation for God’s rescue

- Israel’s descent into self-destruction

Structure

Judges 1-2: Israel’s Moral Compromise in the Promised Land

The opening section begins with the tribes of Israel in their territories within the promised land. While Joshua defeated some key Canaanite towns, there was still a lot of land to be taken and a lot of Canaanites still living in those areas. Chapter 1 gives a long list of Canaanite groups that Israel failed to drive out from the land.

Now remember, the whole point of driving out the Canaanites was to avoid the influence of their moral corruption and the worship of their gods through child sacrifice. God had called Israel to be a holy people, but that did not happen. Chapter 2 describes how Israel simply moved in alongside the Canaanites and began to adopt all their cultural and religious practices.

Then, right there in chapter 2, the story stops, and for nearly a whole chapter the narrator gives us an overview of everything that’s about to happen in the rest of the book. This part of Israel’s history was a series of cycles moving in a downward spiral. Israel would become like the Canaanites and would sin against God. God would then allow them to be conquered and oppressed by the Canaanites. Eventually, the Israelites would see the error of their ways and repent, and God would raise up a deliverer, a judge, from among Israel who would defeat the enemy and bring an era of peace. Sooner or later, Israel would sin again, and it would start all over. This cycle provides the literary design and flow of the next section of the book and is repeated for each of the six main judges whose stories are told here.

Judges 3-16: Israel’s Six Judges, Including Gideon and Samson

The stories of the first three judges, Othniel, Ehud, and Deborah, are epic adventures that are extremely bloody. Either the judges themselves or the people helping them defeat their enemies and deliver the people of Israel. The stories about the next three judges are longer and focus on their character flaws, which only get progressively worse.

Gideon (Judg. 6-9) starts out well enough. He’s a coward of a man, but he comes to trust that God can save Israel through him. He defeats a huge army of Midianites with only 300 men carrying nothing but torches and clay pots. Gideon has a nasty temper, however, and murders several of his fellow Israelites for not helping him in battle. To make matters worse, he also makes an idol from the gold he won in a battle, and after he dies, all of Israel worships it as a god, and the cycle begins once again.

The next main judge is Jephthah (Judg. 10-12), who’s something of a mafia thug living in the hills. When things got really bad for Israel, the elders came to him begging for his leadership. Jephthah actually proved to be a very effective leader, as he won lots of battles against the Ammonites. But in the end, he was so unfamiliar with the God of Israel that he treated him like a Canaanite deity and vowed to sacrifice his daughter if he won the battle. This tragic story shows just how far Israel has fallen. They no longer know the character of their own God, which leads to murder and false worship.

The last judge, Samson (Judg. 13-16), is by far the worst. His life began full of promise, but he had no regard for the God of Israel, and he was promiscuous, violent, and arrogant. He brutally won strategic victories over the Philistines, but only at the expense of his integrity. His life comes to an end in a violent rush of mass murder.

Now, a quick note. You’ll notice a repeated theme here where, at key moments, God’s Spirit empowers each of these judges to accomplish great acts of deliverance. The fact that God uses these people does not mean he endorses all or any of their choices. God is committed to saving his people, but all he has to work with are these corrupt leaders. And work with them he does.

This whole section of the book of Judges shows just how bad things have become. You can no longer tell the Israelites and the Canaanites apart—and that’s just the leaders! The final section, on the other hand, shows Israel as a whole hitting rock bottom.

Judges 17-21: Israel Descends Into Self-Destruction

There are two tragic stories here, in chapters 17-18 and 19-21, that are not for the faint of heart. They are structured by a key phrase that gets repeated four times: “In those days, Israel had no king and everyone did what was right in their own eyes” (Judg. 17:6; Judg. 18:1; Judg. 19:1, and 21:25).

The first story is about an Israelite named Micah who builds a private temple to an idol. This temple is then plundered by a private army sent from the tribe of Dan. The soldiers from Dan steal everything, but much worse, they burn the peaceful city of Laish to the ground, murdering all its inhabitants. This is horrifying; when Israel forgets its God, might makes right.

The next story is even worse—a shocking tale of sexual abuse and violence, leading to Israel’s first civil war. It’s very disturbing, and that’s the point. These stories serve as a warning. Israel’s descent into self-destruction is a result of turning away from the God who saved them from slavery in Egypt. Now they need to be delivered again, but this time from themselves.

The only glimmer of hope is found in this repeated line from the last section, which also forms the last sentence of the book: “Israel has no king” (Judg. 21:25). The stage is set for the following books to tell the origins of the family of King David (the book of Ruth) as well as the origins of kingship itself in Israel (Samuel).

The book of Judges has value as a sobering exploration of the human condition, but it ultimately points forward to God’s grace in sending a king who will rescue his people.

Frequently Asked Questions

Here are some of the most common questions people ask online about this book.

Unlike kings, judges did not inherit their position; they were either directly raised up by God or appointed by the people. In the book of Judges, God raises up judges to serve as military deliverers and lead the people in times of crisis, empowering them with his Spirit to fulfill their calling (Judg. 2:18, Judg. 3:9-10). Deuteronomy 16:18 calls the Israelites to appoint judges in every town to uphold “righteous judgment” in disputes and legal matters (see also Exod. 18; Deut. 17:9, Deut. 19:17).

So when the judge Samuel acts like a king by appointing his corrupt sons to succeed him, the Israelites make a good decision to reject their leadership because judges aren’t appointed in this way. Ironically, rather than trusting God for guidance, the people want a human king (like all the nations surrounding them). So they plead with Samuel to appoint a king to rule over them (1 Sam. 8:1-6)—a choice that ultimately goes poorly.

The book of Judges includes 12 judge accounts (which represent the 12 tribes of Israel), divided into six brief judge reports and six longer judge narratives.

Judges Reports:

- Shamgar (Judg. 3:31)

- Tola (Judg. 10:1-2)

- Jair (Judg. 10:3-5)

- Ibzan (Judg. 12:8-10)

- Elon (Judg. 12:11-12)

- Abdon (Judg. 12:13-15)

Judges Narratives:

- Othniel (Judg. 3:7-11)

- Ehud (Judg. 3:12-30)

- Deborah/Barak (Judg. 4-5)

- Gideon (Judg. 6-8)

- Jephthah (Judg. 10:6-12:7)

- Samson (Judg. 13-16)

Elsewhere in the Hebrew Bible, Moses (Exod. 18:13-16) and Samuel (1 Sam. 7:15-17) are also described as judges. And the Israelites appoint many unnamed individuals to serve as judges by resolving disputes among the people (Exod. 18:21-26; Deut. 16:18).

The book of Judges teaches us how God faithfully sticks with people, fulfills his agreements with them, and shows an immense amount of mercy. Even when the Israelites turn away from him again and again, God still responds to their cries for help with loving action, raising up judges to deliver them.

At the same time, the book highlights the consequences of Israel’s repeated choice to turn away from God and to reject his way of life. When they adopt the harmful, corrupting practices of their neighboring Canaanites, God hands them over to the Canaanites.

As the Israelites move further and further away from God’s instruction and instead do what they see as right in their own eyes, the nation spirals into chaos. The final chapters of the book describe tragic violence, moral collapse, and civil war, framed by the refrain, “In those days there was no king in Israel; everyone did what was right in his own eyes” (Judg. 17:6, Judg. 21:25 NASB).

So the book of Judges raises the question: Is Israel’s problem their lack of a human king, or their unwillingness to regard God as their true king? When God gives the people the human king they want (1 Sam. 8), he warns them that kings often follow the same corrupt pattern as the judges, doing what’s right in their own eyes. Ultimately, the book leaves readers reflecting on the limitations of human leadership and the need for divine guidance to bring true justice and peace.

The book of Judges repeats the same plot again and again, like a song on a loop. The cycle begins with the Israelites doing “bad in the eyes of Yahweh” by worshiping other gods (Judg. 2:11, BibleProject Translation). In response, God removes his protection and allows neighboring nations to oppress them. The Israelites then cry out to God in their distress, and God raises up a judge to rescue them. After the judge delivers the people from their enemies, peace follows—until the judge dies. Then the people return to their unfaithfulness, starting the cycle again (Judg. 2:14-19).

In biblical narratives, repeated patterns often serve as rhetorical devices that establish expectations for readers. When the author deviates from that pattern, it signals something noteworthy—an invitation to pay close attention. And we see the pattern breaking in the story of Jephthah (Judg. 11:1-12:7). Unlike other instances where God raises up a judge, in this story, the Israelites appoint their own deliverer—Jephthah. He’s a marauder and an opportunist, driven by fear and survival, who leads a group of “worthless men” (Judg. 11:3, BibleProject Translation).

Still, the story shows God empowering Jephthah with his Spirit (Judg. 11:29) and enabling him to secure victory over Israel’s enemies. God demonstrates his deep compassion for his people by working through flawed leaders like Jephthah to rescue his people, despite their repeated unfaithfulness to him.

But this deviation in the Jephthah narrative also highlights the people’s increasing reluctance to depend on God for good leadership. As the narrative progresses, it becomes clear that the repeating pattern is not just a cycle but a downward spiral, leading Israel deeper and deeper into chaos (see Judg. 17-21).

In the book of Judges, the Israelites repeatedly cry out to God, asking for deliverance from their oppressive enemies. Earlier God rescued the Israelites when he heard their “groaning” (Hebrew ne’aqah) from slavery in Egypt (Exod. 2:24). And now he hears their “groaning” (ne’aqah) once again (Judg. 2:18). The Israelites have turned away from God and chosen instead to trust the gods of their Canaanite neighbors. So God removes his protection from them and allows their enemies to oppress them (Judg. 2:11-15).

Some interpreters see the Israelites’ cries to God as a sign that they’re turning back to follow him with wholehearted devotion. But when they cry out in Judges 6:7-10, it’s clear that they haven’t turned away from worshiping idols. In response to their cry, God raises up a judge named Gideon and instructs him to tear down an altar to the Canaanite god Baal. When Gideon follows through and destroys it, the townspeople get angry and want to kill him (Judg. 6:25-30). At least in this story, “crying out” is less about wholehearted devotion to God and more about simply seeking God’s help.

Only in Judges 10 do the Israelites clearly express remorse for abandoning God in favor of foreign gods (Judg. 10:10). But God does not immediately accept their confession because while he has rescued them again and again, they’ve continued to turn away from him. So now he says they should ask their other gods to save them. Still, when the Israelites demonstrate their sincerity by disposing of their idols, God responds with compassion (Judg. 10:11-16).

The book of Judges reveals God’s generous, relentless mercy towards people. He repeatedly responds to their outcries by delivering them from their enemies, even when they haven’t clearly shown their commitment to him.

In general, Israel’s judges are not prophets. Within the book of Judges, they function primarily as military leaders, delivering the Israelites from their enemies. Elsewhere, judges are appointed to mediate disputes and decide legal matters (Exod. 18:13-26). In contrast, prophets speak on God’s behalf to the people, which often involves warning them about the consequences of turning away from God’s instruction.

However, a few judges also function as prophets. Moses acts as a judge (Exod. 18) and is Israel’s prophet par excellence, whom God speaks to “face to face” (Deut. 34:10; also Deut. 18:15-18). Deborah, the only judge in the book of Judges who decides disputes rather than acting as a military leader, also serves as a prophet, calling Barak to deliver the Israelites from their Canaanite oppressors (Judg. 4:4-9). And Israel’s last judge, Samuel, is a prophet during a time when few people hear from God (1 Sam. 3:1; 1 Sam. 3:1 Sam. 3:19-21; 1 Sam. 7:15-17).

God chooses judges to deliver the Israelites from their enemies. In the book of Judges, the people repeatedly turn away from God, forfeiting his protection, which allows other nations to oppress them. Despite his people’s unfaithfulness, God stays committed to them, answering their cries for help by raising up judges to deliver them.

But the book does not explain why God chooses particular people as judges. They’re often deeply flawed and mirror Israel’s downward spiral into moral chaos, which ultimately leads the nation to the brink of self-destruction. Gideon cowers in fear, Jephthah makes a devastating vow, and Samson impulsively indulges his appetites.

So God doesn’t choose the judges because they’re good examples of how the Israelites should live. But by working through them, God reveals that human failings cannot thwart his power to save and restore his people. And the book of Judges points toward the need for a future leader who will break the cycle of rebellion once and for all.

Ehud is an Israelite judge who delivers his people from the Moabites by pretending to have a secret message for the Moabite king and then thrusting his sword through the king’s ample belly with his left hand (Judg. 3:15-23). But why does Judges specify that Ehud uses his left hand?

This piece of information is central to Ehud’s characterization. When he’s first introduced, the story tells us he’s “left-handed.” (Or perhaps, following the early Greek translation of the Old Testament, he is “ambidextrous.”) It also ironically notes that this left-handed judge is from the tribe of Benjamin, which means “son of my right hand,” perhaps suggesting that he will defy expectations.

Men who could use their left hand in battle would have a distinct advantage in combat with primarily right-handed soldiers. Judges 20:16 describes an elite contingent of 700 left-handed (or ambidextrous) Benjaminite troops, who could sling stones with deadly accuracy.

And Ehud’s ability to use his left hand may explain how he’s able to sneak his weapon into the palace. A dagger would typically be sheathed on the left thigh and drawn with the right hand. So the dagger on his right thigh (see Judg. 3:16) escapes the notice of the guards, giving Ehud the element of surprise as he approaches the Moabite king.

In the book of Judges, the character of the judges matches that of the people—both struggle to follow God and spiral downward into horrific violence. The judge portrayed most positively is Deborah. She demonstrates immense courage and trusts that God will deliver his people’s enemies into their hands (Judg. 4:6-7). And, like Moses and Miriam, she celebrates their victory with a song commemorating God’s deliverance (Judg. 5; see Exod. 15:1-21).

Gideon is introduced as a fearful character who’s reluctant to trust God’s promises, asking for multiple signs (Judg. 6:16-21; Judg. 6:36-40). Although he miraculously delivers his people with a tiny army of 300 men, his life is marked by contradiction. He nobly refuses an offer of kingship, saying that God alone will rule over Israel (Judg. 8:23). But he acts just like a Canaanite king, executing unwarranted brutality (Judg. 8:4-17), leading Israel deeper into idolatry (Judg. 8:24-27), and even naming one of his many sons Abimelech, which means “my father is king” (Judg. 8:30-31).

Jephthah brings down tragedy on his household with a rash vow. He declares that if God gives him victory over his enemies, he will sacrifice to God the first thing he sees coming out of his house when he returns home. Yet, it ends up being his only daughter (Judg. 11:30-34). Rather than protecting the life of his daughter and accepting the consequences of breaking his vow (see Deut. 23:21), he offers her up as a sacrifice to God (Judg. 11:39-40)—a clear violation of the law (Lev. 20:2-5; Deut. 12:31).

The book’s final judge, Samson, seems far more interested in serving his appetites for women and vengeance than in serving God (Judg. 14-16). Even his climactic act of deliverance—where he kills 3,000 Philistines as well as himself by breaking the pillars of an idolatrous temple—is motivated by a desire for revenge, rather than concern for his suffering people (Judg. 16:23-30).

The book of Judges demonstrates God’s willingness to work through human failings to rescue his people. And it raises the hope that one day a faithful leader will come and guide Israel to follow God’s wisdom.