The Book of Micah

About

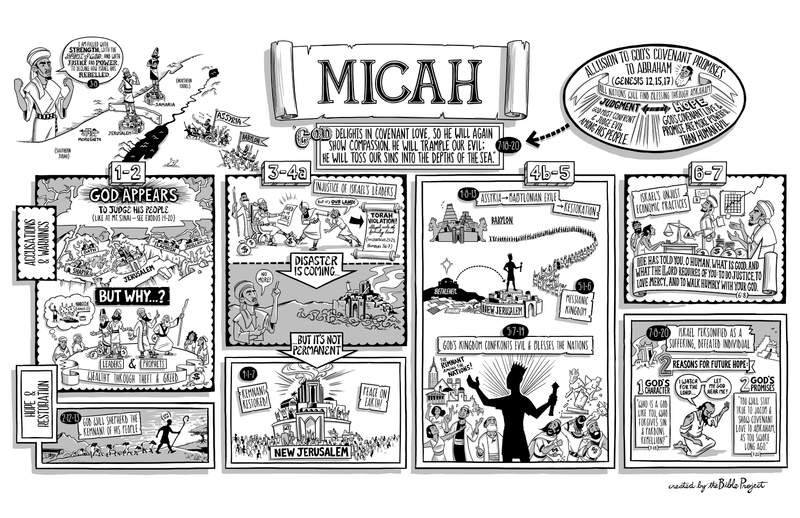

One important aspect of the ancient TaNaK order of the Hebrew Bible is that the 12 prophetic works of Hosea through Malachi, sometimes referred to as the Minor Prophets, were designed as a single book called The Twelve. Micah is the sixth book of The Twelve.

Micah lived in the small town of Moresheth in the southern kingdom of Judah at the same time Isaiah was alive in Jerusalem. The northern and southern kingdoms had split long ago, and both had been violating their covenant with the God of Israel. Micah warned that God would allow the empire of Assyria to take out the north and ravage Jerusalem, and that after them, Babylon would bring even more destruction. Like all the prophets, Micah spoke on God’s behalf to accuse Israel, or, as he puts it in chapter 3, “I am filled with strength, with the Spirit of God, and with justice and power, to declare how Israel has rebelled” (Mic. 3:8).

Most of this book explores Micah’s accusations and warnings of God’s impending judgment on Israel, but Micah also had a message of hope that countered these warnings and told of the restoration that God would one day bring about.

Who Wrote the Book of Micah?

Context

Key Themes

- God’s accusation of injustice toward Israel and hope for the future

- God’s promise to not abandon his people

- Covenant renewal through the messiah

- Forgiveness of sins and restoration from exile

Structure

Micah 1-4a: Accusing Israel’s Leaders of Injustice

The first two sections of the book of Micah develop the prophet’s accusations and warnings against Israel and its leaders. Chapter 1 opens with a poetic description of God appearing over Israel, just like he did at Mount Sinai—with fire, smoke, and earthquake. Unlike the time at Mount Sinai, God hasn’t come to make a new covenant. Instead, he will bring judgment on them for over 500 years’ worth of rebellion. Micah proceeds to go down a list of towns and cities in Israel, like Shapir, Gath, Jerusalem, Lachish, and Adullam, that were the culprits of all this rebellion, and he says that God is coming for them. But why exactly?

Micah is picking a fight with Israel’s leaders. He says that they’ve become wealthy through theft and greed, alluding to the story of Ahab stealing a family vineyard from Naboth (1 Kgs. 21). Even Israel’s prophets are corrupt, as they are quite happy to offer promises of God’s protection to anyone who can pay them. As a result, Micah tells them that God has withdrawn his protection from Israel.

In chapters 3-4, Micah describes in a second set of accusations even more ways that the leaders and prophets have worked together to create grave injustices. They run the land with bribes and bend the law to favor the wealthy, depriving the poor of their land, their security, and eventually, their hope. This is all in violation of the laws of the Torah, which declared it illegal to sell land belonging to families, including poor ones. God’s judgment will take the form of oppressive nations coming to take out the northern kingdom, Jerusalem, and their temple.

While these are severe warnings, the book doesn’t end things there. Each section of warning is concluded with a striking promise of hope. The first of these is a poem about how God is like a shepherd who’s going to rescue and regather his flock, the remnant of his people (Mic. 2:12-13).He’ll bring them to good pastures and become their king once more. The second promise is found in chapter 4, where Micah picks up on the image of the ruined Jerusalem temple and says that it won’t be permanent. God will one day exalt his temple, fill it with his presence, and fill the city with the remnant of his people. God’s purpose, to make Israel the meeting place of Heaven and Earth, will be fulfilled, and all nations will stream to Jerusalem, where God will become their King and bring peace to all the Earth.

Micah 4b-5: Hope for Restoration Under the Messianic King

These two poems of hope are very powerful already, and the next section of the book develops their themes further with another set of beautifully designed poems. In Micah 4:8-13, we learn that after the Assyrian attack, Israel will be exiled to Babylon, but God will eventually restore his people and bring them back to their land. In Micah 5:1-6, we learn that a new messianic king from the line of David will come to the new Jerusalem. He’ll be born in Bethlehem and will rule in Jerusalem over the restored people of God. Finally, in Micah 5:7-14, we see that in the messianic Kingdom of God, the faithful remnant of God’s people will be a blessing among the nations. This is when God will bring his final justice and remove evil from the world.

Micah 6-7: Hope in God’s Mercy and Redemption

The final section of the book returns to the same pattern used in the first part—warning followed by hope (chs. 6-7). Micah exposes the unjust economic practices of Israel’s leaders that are destroying both the land and the people. It’s here that Micah offers his famous words summarizing what it means for Israel to follow their God. “He has told you, O human, what is good, and what the Lord requires of you: to do justice, to love mercy, and to walk humbly with your God” (Mic. 6:8). Israel has not been doing any of this and so will come to ruin.

However, the book ends on another powerful note of hope. Israel is personified as an individual, sitting alone in shame and defeat. It’s clearly an image of Israel’s destruction and exile. The poet is watching for God’s mercy, begging God to listen and forgive him—but why? Why should God do this for a faithless and rebellious people? The poet offers two reasons. First, because of God’s character. “Who is a God like you, who forgives sin and pardons rebellion?” (Mic. 7:18) Micah knows that God’s mercy is more powerful than his anger or judgment. The second reason is because of God’s promises. “You will stay true to Jacob, and show covenant love to Abraham, as you swore long ago” (Mic. 7:20).

These are the final words of the book, and they’re an allusion to God’s covenant promises to Abraham’s family all the way back in Genesis 12; Genesis 15, and 17, that all nations will find God’s blessing through Abraham and his family. In order to become this blessing, however, Israel must be faithful to their God. This explains all the back and forth between judgment and hope in the book of Micah. If God’s going to bless the nations through Israel, then he must first confront and judge the evil among his people. And so God’s judgment is actually a source of hope because his covenant love and promise are more powerful than human evil. God’s ultimate purpose is not to destroy but to save and redeem. As the concluding lines of the book put it, God “delights in covenant love, so he will again show compassion, he will trample our evil, he will toss our sins into the depths of the sea” (Mic. 7:18-20).

That’s what the book of Micah is all about.