The Book of Psalms

About

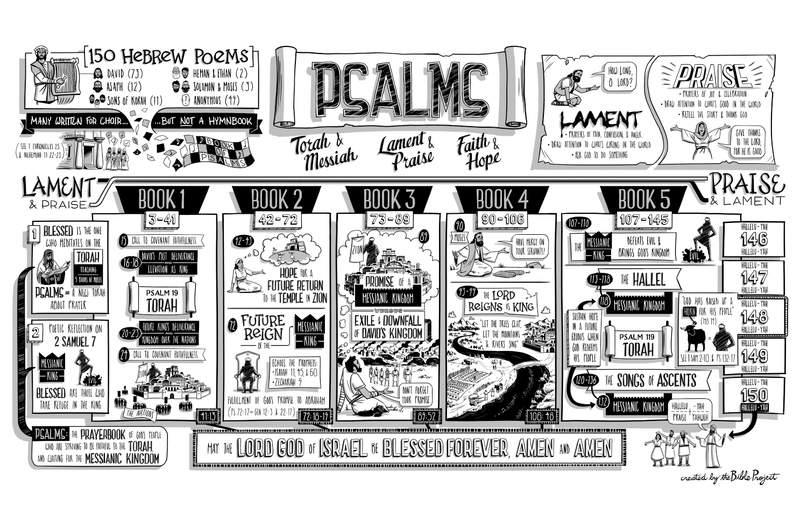

Psalms is a collection of 150 ancient Hebrew poems, songs, and prayers that come from different eras in Israel’s history. Seventy-three of these psalms are connected to King David, who was a poet and harp player (1 Sam. 16; 2 Sam. 23). There were also many other authors involved. Asaph wrote 12 poems, the sons of Korah produced 11, and other worship leaders in the temple contributed as well (Heman and Ethan wrote one each; see 1 Chronicles 15:17-19). Two are connected to King Solomon and one other to Moses. Nearly one-third of the poems (49, to be exact) are anonymous.

Many of these poems were used by Israel’s temple choirs (1 Chronicles 25; Neh. 11:22-23), but the book of Psalms is not actually a hymnbook. In the period after Israel’s exile to Babylon, these ancient songs were gathered together with many other Hebrew poems and intentionally arranged into the book of Psalms. The entire work has a unique design and message that you won’t notice unless you read it beginning to end.

Who Wrote the Book of Psalms?

Context

Key Themes

- God as King of all creation

- Hope for the Messiah after exile

- Lament as a response to evil

Structure

The Overall Design of the Book of Psalms

To see the book’s overall design, it’s actually helpful to start at the end. The book concludes with five poems of praise to the God of Israel (Ps. 146-150), each beginning and ending with the word “hallelujah.” In Hebrew, this word is a command telling people to “Praise Yah,” which is an abbreviation of the divine name, Yahweh. This neat, five-part conclusion looks very intentional and invites the question of whether other parts of this book have been designed.

If you pay close attention to the headings of the poems, you’ll notice that in five different places, Bible translators included the headings Book One through Book Five. The whole book of Psalms has been divided into five books or sections (Ps. 3-41; Ps. 42-72; Ps. 73-89; Ps. 90-106, and 107-145). The reason for these divisions is that each section has a final poem, which concludes with a similar line that looks like an editorial addition, “May the Lord, the God of Israel, be blessed forever. Amen and Amen” (Ps. 41:13; Ps. 72:19; Ps. 89:52, and 106:48).

Psalms 1-2: Introduction to the Key Themes of Psalms

The book has a conclusion and an internal organization of five sections. Psalms 1 and 2 serve as the book’s introduction. These psalms clearly stand apart from the rest of Book One based on their authorship. They are anonymous, while the majority of psalms in the first book are linked to King David. Their content is also unique. Psalm 1 starts by celebrating the person who is “blessed” because they meditate on the Torah, prayerfully reading and obeying it. The Hebrew word torah simply means “teaching,” but it also refers to the first five books of the Bible that contain the foundational laws of Judaism. It seems that the word has both of these meanings in Psalm 1. The book of Psalms is being offered as a new Torah that will teach God’s people about the lifelong practice of prayer as they strive to obey the commands of the first Torah.

Psalm 2 is a poetic reflection on God’s promise to King David, recounted in 2 Samuel 7. God told David that from his line would come a messianic (that is, “anointed”) King, who would establish God’s Kingdom over the world, defeating evil and rebellion among the nations. The psalm concludes by saying that all those to take refuge in this messianic king will be “blessed,” the same word used in the opening of Psalm 1.

Together, these two poems tell us that the book of Psalms is designed to be the prayer book of God’s people, who are striving to be faithful to the commands of the Torah and hoping and waiting for the messianic kingdom.

Psalms 3-41: The Foundation of Covenant Faithfulness

With these themes introduced, we can begin to see intentionality in how the smaller books have been designed around the same ideas. For example, Book One contains a collection of poems (Ps. 15-24) that opens and closes with a call to covenant faithfulness. The opening Psalm 15 is followed by three poems (Ps. 16-18) that depict David as a model of such faithfulness, calling out to God for deliverance and being rewarded and elevated as king. These three have a symmetrical pair in Psalms 20-23, where the David of the past has become an idealized image of the future messianic king, who will call upon God for deliverance and be rewarded with a kingdom over all nations. And right in the center of this collection is Psalm 19, a poem dedicated to praising God for the gift of the Torah. This is a great example where we see that the twin themes from Psalms 1 and 2 emerge with intentional clarity.

Psalms 42-72: Hope for the Messianic Kingdom

Book Two (Ps. 42-72) opens with two poems united in their hope for a future return to the temple in Zion (Ps. 42-43), an image closely associated with the hope of the messianic kingdom. Book Two closes with a corresponding poem that depicts the future reign of the messianic king over all nations (Ps. 72). This poem echoes many other passages in the Prophets about the messianic kingdom (Is. 11, 45, 60; Zech. 9) and concludes by saying that this king’s reign will bring the fulfillment of God’s promise to Abraham by bringing God’s blessing to all nations (Ps. 72:17; see Gen. 12:3; Gen. 22:17-18).

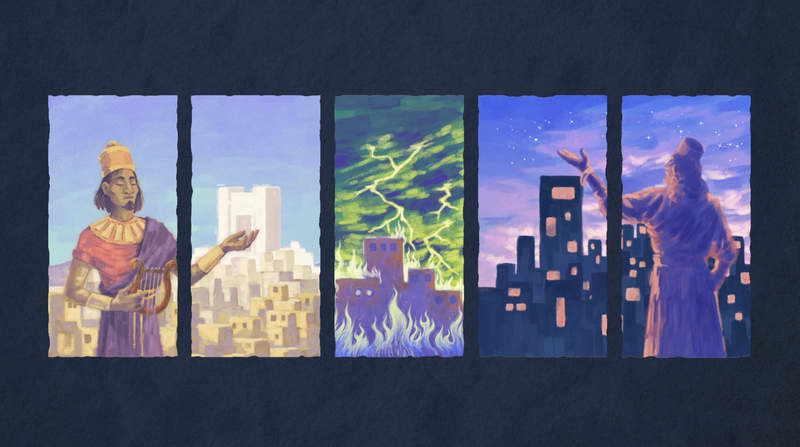

Psalms 73-89: Hope for the Messiah After Exile

Book Three (Ps. 73-89) also concludes with a poem reflecting on God’s promise to David (Ps. 89), but this time in light of the tragedy of Israel’s exile. The poet remembers how God said he would never abandon the line of David. But how does that promise align with Jerusalem’s destruction and the downfall of David’s line? The poem concludes (Ps. 89:49-51) by asking God to remember his covenant with David and to forgive his people.

Psalms 90-106: The God of Israel as the King of All Creation

Book Four (Ps. 90-106) is designed to respond to this crisis. In the opening poem, we return to Israel’s roots with a prayer of Moses (Ps. 90), describing his plea for God’s mercy after the golden calf incident. The center of Book Four is dominated by a group of prayers (Ps. 93-99) that announce the Lord God of Israel as the true King of all creation. The trees, mountains, and rivers are summoned to celebrate the future day when God will bring his healing justice and Kingdom over all the world.

Psalms 107-150: Songs of Ascent and Poems of Praise

Book Five (Ps. 107-145) opens with a series of poems (Ps. 107-110) that affirms that God hears the cries of his people and will one day send the future King to defeat evil and bring about his Kingdom. It also contains two larger collections called the “Hallel” (Ps. 113-118) and the “Songs of Ascents” (Ps. 120-136), both of which conclude with poems about the hope of the messianic kingdom (Ps. 118 and 132). Right between these collections is Psalm 119, the longest poem in the book of Psalms. It is composed in the order of the Hebrew alphabet and explores the wonder and beauty of the Torah as God’s word to his people. We see the themes from Psalms 1 and 2, the Torah, and the messianic hope combined here in Book Five.

This brings us all the way back to the final, five-poem conclusion to the book of Psalms. In the center, Psalm 148 says that all creation is summoned to praise the God of Israel because he has “raised up a horn for his people” (Ps. 148:14). This is a metaphor of a bull’s horn raised in victory. The image echoes back to the same metaphor used in Hannah’s song (1 Sam. 2:10) and earlier in Psalm 132:17. The horn is a symbol of the messianic king and his victory over evil—a fitting conclusion to this book.

Poems of Lament and Praise in the Book of Psalms

There’s one thing about the book of Psalms that’s easy to miss if you don’t read it in order. While there are many different types of poems in the book, they can all be sorted into two larger categories of either lament or praise. Poems of lament express the poets’ pain, confusion, and anger surrounding the horrible things happening around them or to them. They draw attention to what’s wrong in the world and ask God to do something about it. There are a lot of these lament poems in the book, which shows that this is an appropriate response to the evil and tragedy we see in the world. Lamentation plays an important role in our journey of prayer.

While these lament poems make up much of Books One through Three, you can see that praise poems are occasionally woven in as well. These are poems of joy and celebration that draw attention to what’s good in the world. They retell stories of what God has done in the lives of his people, and they thank him for it. In Books Four and Five, praise poems outnumber the laments, culminating in the five-part hallelujah conclusion.

This shift from lament to praise is profound, and it tells us something about the nature of prayer according to this new Torah. Hoping for the messianic kingdom creates tension as we see the tragic state of our world. The Psalms teach us to neither ignore our pain nor let it determine the meaning of our lives. Biblical faith and prayer is always forward-looking, anticipating the day when God will fulfill his promises and praising him for this ahead of time. The Torah and messiah, lament and praise, faith and hope, this is what the book of Psalms is all about.