The Book of Zechariah

About

One important aspect of the ancient TaNaK order of the Hebrew Bible is that the 12 prophetic works of Hosea through Malachi, sometimes referred to as the Minor Prophets, were designed as a single book called The Twelve. Zechariah is the 11th book of The Twelve.

Zechariah is set after the return of the exiles from Babylon to Jerusalem. We are told in the book of Ezra (Ezra 5:1-2) that Zechariah and Haggai together challenged and motivated the people to rebuild the temple and look for the fulfillment of God’s promises. Long ago, Jeremiah the prophet said that Israel’s exile would last for 70 years (Jer. 25:1; Jer. 29:10) and that afterwards God would restore his presence to a new temple. That’s when God would bring his Kingdom and the rule of the messiah over all nations (Jer. 30-33). The dates at the beginning of this book tell us that the 70 years were almost up, but life back in the land was hard, and it seemed like none of these hopes were ever going to be fulfilled. The book of Zechariah offers an explanation about what went wrong.

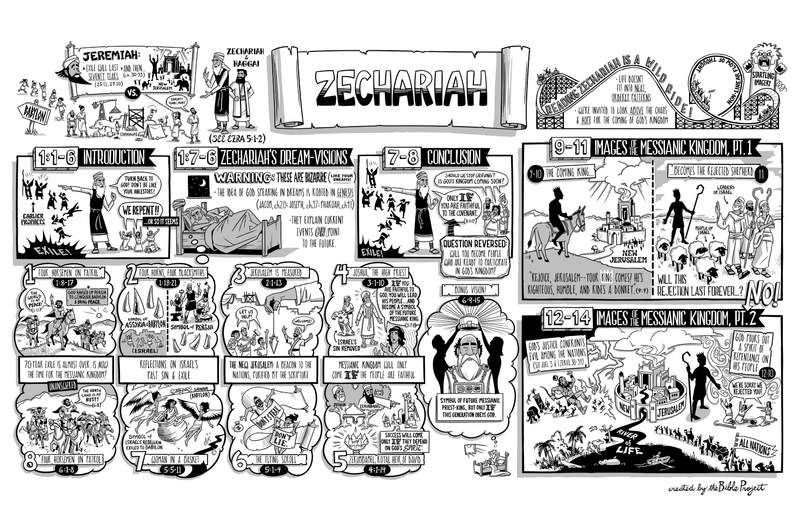

The book has a fairly clear literary design. There’s an introduction that sets the tone for a large collection of Zechariah’s dream-like visions in chapters 1-6. The dreams are concluded in chapters 7-8 and followed by two more collections of poetry and prophecy in chapters 9-11 and 12-14, respectively. Let’s dive in and see how it all works.

Who Wrote the Book of Zechariah?

Context

Key Themes

- The coming of the messianic Kingdom

- An invitation for Israel to be faithful

Structure

Zechariah 1:1-6: A Challenge to Repent

The book begins with Zechariah’s challenge to his generation to turn back to God and not act like their ancestors who rebelled and refused to listen to the earlier prophets. That rebellion is what landed them in exile. The people’s response to Zechariah was ideal, as they repented and humbled themselves before God—or so it seemed.

Zechariah 1:7-6:15: Dream Visions on Exile and Rebuilding

The next section of the book of Zechariah is a collection of eight visions that the prophet experienced. Just to prepare you, these are full of bizarre and strange images, just like your own dreams. The idea that God communicates to people through symbolic dreams is an old one, going all the way back to Genesis. The dreams of Jacob in Genesis 28, Joseph in Genesis 37, and Pharaoh in Genesis 41 all gave meaning to current events or offered a window into the future.

Zechariah’s dreams have been arranged in a really cool symmetrical structure. The first and last visions (Zech. 1:8-17; Zech. 6:1-8) are about four horsemen, who are like rangers patrolling the world on God’s behalf. They represent God’s attentive watch over the nations, and their report is that the world is at peace (Zech. 1:11; Zech. 6:8). In Zechariah’s day, God raised up Persia to conquer Babylon and bring relative peace. The question arises, if the 70 years of Israel’s exile are nearly up, and if there’s peace, isn’t now the time for the messianic Kingdom in Jerusalem? God responds by saying that he will fulfill those promises, but he leaves the issue of timing strangely unanswered.

The second and seventh visions (Zech. 1:18-21; Zech. 5:5-11) are paired as reflections on Israel’s past sin that led to the exile. The second vision is about four horns that symbolize the nations that attacked and scattered Israel. Like Assyria and Babylon, those empires were themselves scattered by a group of blacksmiths, an image of Persia. The matching seventh dream is about a woman in a basket. We’re told that she is a symbol of the centuries of Israel’s covenant rebellion, and she is promptly carried to Babylon by other women with stork wings (so bizarre!).

The third and sixth visions (Zech. 2:1-13; Zech. 5:1-4) are paired as they both focus on the rebuilding of a new Jerusalem. The third dream depicts a man measuring the city. It’s an image of God’s promise that Jerusalem will be rebuilt and become a beacon to the nations who will join God’s people in worship. In the sixth vision, a scroll flies around the new Jerusalem punishing thieves and liars, the idea being that the new Jerusalem is a place purified from sin by the Scriptures.

The fourth and fifth visions (Zech. 3:1-10; Zech. 4:1-14) are at the center of the dream section. They are about the two key leaders among the returned exiles: Joshua, the high priest, and Zerubbabel, a royal descendant of David. Joshua was symbolically wearing Israel’s sin in the form of dirty clothes, but in the fourth dream those are taken off, and he’s given new clean clothes and a turban as a symbol of God’s grace. An angel tells Joshua that if he remains faithful to God, he will lead his people and become a symbol of the future messianic king.

The fifth vision is of two olive trees that supply oil to an elaborate gold lamp. The lamp is a symbol of God’s watchful eye over his people, while the two trees symbolize the anointed leaders Joshua and Zerubbabel, who are leading the temple rebuilding efforts. God says, however, that success won’t come to the new temple if it’s only the result of political maneuvering; rather, these two must be dependent on the work of God’s Spirit (Zech. 4:6).

The dreams conclude with a short bonus vision from Zechariah in 6:9-15. This vision picks up the themes of the central fourth and fifth visions. Joshua the priest is given a crown and is presented as a symbol of the future messiah, who will also be a priest in God’s Kingdom. However, Zechariah says, all this will be fulfilled only if the current generation is faithful to God and obeys the terms of the covenant. All together, these three visions emphasize how the coming of the messianic kingdom is conditional upon this generation becoming faithful to God.

Zechariah 7-8: Invitation to Participate in God’s Kingdom

This leads up to the conclusion of the dream visions with another challenge in Zechariah 7-8. A group of Israelites come, and they have been mourning over the former temple’s destruction for nearly 70 years. They ask, “Should we stop grieving? Is God’s Kingdom coming soon?” In response, Zechariah again reminds them of how their ancestors rejected God’s call through the prophets, which led to the exile (Zech. 7:4-14). He repeats this ancient prophetic challenge in chapter 8. This generation will see the messianic kingdom, but only if they pursue justice and peace and remain faithful to the covenant. In other words, Zechariah reverses their question and asks, “Will you become the kinds of people who are ready to receive and participate in God’s coming Kingdom?”

The question is left hanging as the people don’t answer, and the book just moves on.

Zechariah 9-14: Images of the Messianic Kingdom

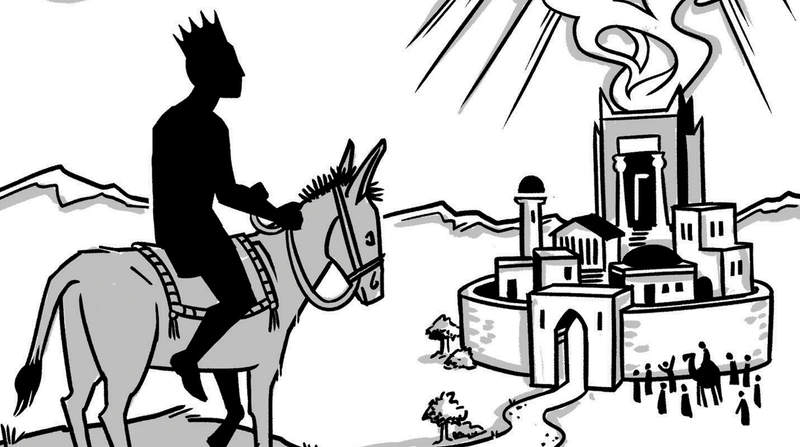

The two final sections (Zech. 9-11; Zech. 12-14) are very different from the first eight chapters. Each one is a kaleidoscopic collage of poems and images about the future messianic kingdom. The first (chs. 9-11) describes the coming of a humble messianic king riding a donkey into the new Jerusalem to establish God’s Kingdom over the nations. The king is then symbolized as a shepherd over the flock of Israel. He is rejected by his own people and their leaders, who are also symbolized as shepherds. As a form of discipline, God hands Israel over to those corrupt leaders. This then raises the question, will Israel’s rejection of their shepherd king last forever?

The final section (chs. 12-14) answers with a clear no. It’s another mosaic of poems and images about the future messianic kingdom. With imagery very similar to the poetry of Joel and Ezekiel, these chapters depict the new Jerusalem as the place where God’s justice will finally confront and defeat evil among the nations. However, God will also confront the rebellion of his own people. He’s going to pour out his Spirit upon them, so that they repent and grieve over the fact that they rejected their messianic shepherd. The final chapter 14 concludes with the new Jerusalem as the gathering point for all the nations. The city becomes a new garden of Eden, with a river of living water flowing out of the temple to bring healing to all creation.

And that’s where the book ends. Zechariah leaves you to ponder the connection between chapters 1-8 and 9-14. The point seems to be that the future Kingdom of the book’s second half will only come when God’s people are faithful to the covenant as the first half made clear.

Reading the book of Zechariah is a wild ride. These visions and poems are full of startling imagery, and they don’t really follow a linear flow of thought. That’s actually part of the point. It’s like history or our own lives, which don’t always fit into neat, orderly patterns. The prophets offer us glimpses of God’s hand at work, guiding history towards his purpose. So, ultimately, Zechariah invites us to look above the chaos and hope for the coming of God’s Kingdom, which should motivate faithfulness in the present moment. That’s the challenge Zechariah offers to all generations of God’s people.