The Books of Chronicles

About

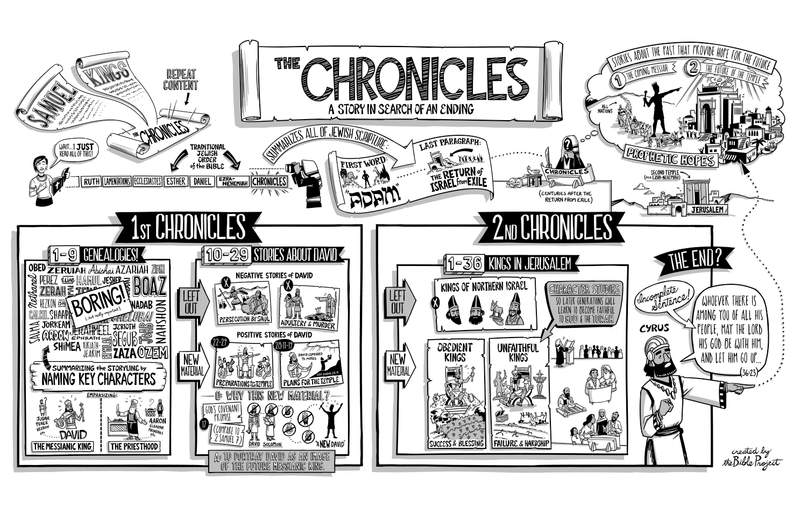

While they are two separate books in our modern Bibles, Chronicles was originally written as one coherent story. It was only divided later due to scroll length. Another important detail is that the books’ current location in the Christian Bible is different from their original location. In most English Bibles, Chronicles comes right after the books of Samuel and Kings. However, most of Chronicles repeats the content of those books, and so many people start reading and think, “Wait, I just read all of this!” And they end up skipping it.

That’s a shame because this is a really unique and important book in the Old Testament with a very intentional design. In the traditional Jewish order of the Bible, Chronicles is actually the very last book because it summarizes all of the Jewish Scriptures. It begins with the first word Adam, the name of the first human character in the beginning of the Scriptures, and it goes all the way through to the last paragraph announcing the return of Israel from exile.

Who Wrote the Books of Chronicles?

Context

Key Themes

- Hope for the Messiah and the new temple

- Kingdom of God

- The exile and return from exile

Structure

Background of the Book of Chronicles

Now, we don’t actually know who wrote the books of Chronicles, but we can tell from certain details that it was written by somebody who lived a couple hundred years after the Israelites returned from the Babylonian exile. For this author, Jerusalem and the second temple were rebuilt some time ago, but as we learn from Ezra-Nehemiah, things were not going well. The great prophetic hope was that the city and temple would be rebuilt. God would come to live among his people, the messianic king would come, and all nations would come together under his peaceful rule. It was very clear to everyone in Jerusalem, including this author, that none of this had happened yet.

In response, the author of Chronicles has shaped the ancient stories of David and Solomon from the past to provide a message of hope for the future. The books have been designed to emphasize two clear themes: the hope of the coming messianic king and the hope for a new temple.

1 Chronicles 1-9: Genealogies of Kings and Priests

1 Chronicles begins with nine chapters of genealogies, long lists of names and family lines. While you read these, you may think that it’s all very boring, which is kind of true, but these chapters are actually really important! Through them, the author is summarizing the entire Old Testament storyline by naming all the key characters.

The author has shaped these genealogies to emphasize two particular lineages connected to the two main themes. The first is the line of the promised messianic king. Lots of space is dedicated to tracing the line of Judah leading to King David, to whom the messianic promise was given. That line is then traced forward to the author’s own day. The other family line that gets a lot of emphasis is that of the priesthood, the descendants of Aaron who worked in the Jerusalem temple. So right from the start, you can see the two main themes of the books of Chronicles (hope for the Messiah and the new temple) are rooted deeply in these ancient genealogies.

1 Chronicles 10-29: King David as the Messianic Ideal

From here, we move into stories about David (1 Chron. 10-29), and while most of these will be familiar from reading the book of Samuel, there are some very important differences. First of all, the author leaves out all the negative stories in which David is portrayed as weak or immoral. Saul chasing him around the desert and persecuting him, the story of David’s adultery with Bathsheba, and the following murder of her husband—all of that’s gone. We are left only with the stories that portray him as a good guy.

There is also new material that shows David in a very positive light. There’s a large block of chapters (1 Chron. 22-29) in which David makes preparations for the first temple, arranging for builders, Levites, and choirs. The author even goes so far as to portray David as a figure like Moses. God gives David the plans for building the temple, just as he gave plans to Moses for the tabernacle (compare 1 Chronicles 28:11-19 with Exodus 25:9).

So why is there all this new material about David? The author is certainly not trying to hide David’s flaws. He knows that anyone can go and read about them in the books of Samuel. It seems instead that the author is trying to portray David as an ideal king in order to create a narrative prophecy that points to the image of the future messianic king. This is very similar to the ways that Jeremiah and Ezekiel spoke of the coming messiah as “a new David” (Jer. 30:9; Ezek. 37:25).

This idea becomes clearer when you read the story of God’s covenant promise to David in 1 Chronicles 17 and compare it to its earlier parallel in 2 Samuel 7. The author of Chronicles definitively highlights the fact that neither David, Solomon, nor any of the kings from that line were the messianic king. But when that messiah does come, he will be a king like the idealized David of these stories. For the author, these classic stories of David from the past are really glimpses into the future Kingdom of God.

2 Chronicles 1-36: Judah’s Kings and an Unfinished Story

As we continue into 2 Chronicles, we find a lot of overlap with 1 and 2 Kings, but, once again, there are a few key differences. The author has left out all the stories of the kings in northern Israel and instead continues his focus on the line of David. There is a lot of new material and stories about these Davidic kings, and the author specifically highlights those who were obedient to God and gained success and blessing. The author also supplies new stories about kings who were unfaithful to God. Those who failed to follow the Torah and led Israel into idol worship faced horrible consequences and ultimately brought about the Babylonian exile. And it was all a mess of their own making.

This whole section becomes a series of character studies for later generations. The author wants all of God’s people to learn from their family history and become faithful to their God and to the Torah.

The book’s conclusion is unique, too. At the very end of the book, Cyrus, the king of Persia, tells the Israelites that they can return from exile and rebuild the temple in Jerusalem. He says, “Whoever there is among you of all his people, may the Lord his God be with him, and let him go up…” (2 Chron. 36:23).

That’s actually how the book ends, with an incomplete sentence (it’s even more awkward in Hebrew than in English). Now, of course, the author knows about the first return from exile and the stories of Ezra and Nehemiah, but clearly, in his view, the prophetic hopes of Israel were not fulfilled in those events. This incomplete ending shows that the author’s hope is set on yet another return from exile, when the Messiah will come to rebuild the temple and restore God’s people.

So the books of Chronicles, the final books in the Jewish Scriptures, end by pointing forward. They call upon God’s people to look back in order to look ahead because the past is the source of hope for the future. Chronicles concludes the Old Testament as a story in search of an ending.