The Book of Joshua

About

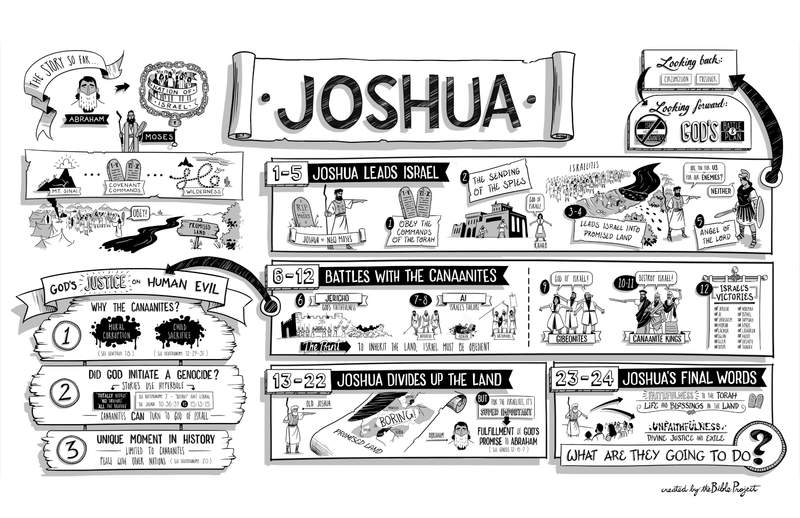

Before looking at the book of Joshua, let’s back up and remember the story of the Bible so far. God chose Abraham to bring his blessing to the nations. Abraham’s family grew and became the people of Israel, and after some time, they were enslaved in Egypt. Through Moses, God rescued the Israelites and brought them out of Egypt to Mount Sinai where he made a covenant with them. Then, God brought the people through the wilderness despite the hardships and rebellions along the way. Finally, as Israel camped outside the promised land, Moses called upon them to obey God’s commandments, so that they could show the other nations the true character of God. The book of Joshua picks up shortly after Moses dies as Israel prepares to enter the land.

The storyline of Joshua is designed with four main movements. Joshua leads Israel into the promised land (Josh. 1-5). Once they’re there, they are met with hostility from the native Canaanites, and they engage in battle (Josh. 6-12). After their victories, Joshua divides up the land as an inheritance for the twelve tribes (Josh. 13-22), and finally, the book concludes with Joshua delivering his final words to the people (Josh. 23-24).

Who Wrote the Book of Joshua?

Context

Key Themes

- Israel’s need to trust God for entry into the promised land

- God’s command for Israel to pursue peace with other nations

- God’s eradication of human evil and upholding of justice

- The generosity of God for protection and rescue

Structure

Joshua 1-5: Israel Enters the Promised Land

Chapter 1 begins with Moses’ death and the appointment of Joshua as the new leader of Israel. The author intentionally presents Joshua as a new Moses. Like his predecessor, Joshua calls on the people to obey the terms of the covenant given to Israel at Mount Sinai that are found in the Torah. In chapter 2, Joshua sends spies into the land, just as Moses had in Numbers 13-14. Things go much better this time, and even some Canaanites, such as Rahab the prostitute, turn to follow the God of Israel. Joshua then leads all of Israel across the Jordan River and into the land. Just as the sea parted for Moses in Exodus, so here the river parts as priests carrying the ark of the covenant lead the Israelites across to the land.

The story transitions in chapter 5 as the Israelites look back to their roots as God’s covenant people. They have the new generation circumcised to honor that covenant, and they celebrate their first Passover in the new land. Just as they prepare to go forward, Joshua has an encounter with a mysterious warrior who, it turns out, is the angelic commander of God’s army. Joshua asks, “Are you for us or for our enemies?” The warrior responds, “Neither,” which shows that the real question is whether Joshua is on God’s side. Chapter 5 makes clear that this story will not be about the Israelites versus the Canaanites. Rather, it is God’s battle. Israel will play the role of spectators and only sometimes act as supporters in his purposes.

Joshua 6-12: Victorious Battles Over the Canaanites

This leads into the next section of the book of Joshua, in which we find stories about all the conflicts Israel had with different Canaanite groups as they entered the land. Chapters 6-8 retell the story of two battles in detail, followed by chapters 9-12, which are a series of short stories that condense years of battles into a few brief summaries.

The first two battles against Jericho and Ai offer contrasting portraits of God’s faithfulness and Israel’s failure. At Jericho, Israel is to take a completely passive approach, letting God’s presence in the ark lead them around the city with music for six days. Just as Rahab turned to the God of Israel, perhaps the people of Jericho will do the same. They do not, sadly, and so on the seventh day when the priests blow their trumpets, the walls miraculously crumble and Israel is led to victory. The point of this story is that God is the one who will deliver his people. Israel simply needs to trust and wait.

The battle at Ai makes a contrasting point, showing what happens if Israel doesn’t trust their God. An Israelite named Achan stole goods from Jericho that were meant to be devoted and offered to God. Then he proceeded to lie about it—a pretty selfish move after all that God had done for Israel. So when Israel enters the battle of Ai, they are defeated. It’s only after humble repentance and severely dealing with Achan’s sin that they gain victory over Ai.

Together, these two stories are placed at the front of the battle narratives to make an important point. To inherit the land, Israel has to be obedient and trust in God’s commands. This isn’t their battle, and God isn’t their trophy.

The second part of this section begins in chapter 9 as the Gibeonites, a Canaanite people group, do what Rahab did—turn to follow Israel’s God and make peace. This is in stark contrast to many other Canaanite kings, who form coalitions to destroy Israel. Israel, however, wins all of these battles by a landslide. The section concludes with a summary list of all the victories won by Moses and Joshua (Josh. 12).

Now, let’s stop for a moment because odds are that these stories and the violence described in the battles are going to bother you. If you’re a follower of Jesus, you’re bound to wonder, “Didn’t Jesus say, ‘love your enemies’? Why is God declaring war?”

First of all, why the Canaanites? The main reasons given are that their culture had become morally corrupt, especially when it came to sex (Lev. 18), and because they widely practiced child sacrifice (Deut. 12:29-31). God didn’t want these practices to influence Israel, so these groups needed to be expelled.

But that only raises the second question, “Did God really command the destruction of all the Canaanites, like a genocide?” At first glance, we see the phrases “totally destroy” and “leave no survivor” or “anything that breathes.” However, when we look more closely, we discover that these phrases are used by the author as hyperbole and are not meant literally.

Look again at God’s original command in Deuteronomy 7. Israel is first told to “drive out” the Canaanites as well as to “totally destroy” them. This is immediately followed by commands to not intermarry or enter business deals with them. You can’t marry or do business with people that you’ve literally destroyed! Moses is using hyperbole, an exaggerated expression, to make his point with force.

The same idea applies to the stories told in Joshua. For example, we’re told in Joshua 10:36-39 that Israel left “no survivors'' in either Hebron or Debir, but later in 15:13-15, these towns are still populated by Canaanites. In this way, the stories of Joshua fit in with other ancient battle accounts in their use of nonliteral hyperbole as part of the narrative style.

So the word “genocide” doesn’t really fit with what we see here, especially in light of the stories about Canaanites who did turn to the God of Israel, like Rahab or the Gibeonites. God was very open to all who would turn to him in repentance and trust.

As a last thought, these stories mark a unique moment in history. These battles were limited to the handful of people groups living in the land called Canaan. We know this was a temporary and limited measure because Israel was commanded by God to pursue peace with all other nations (Deut. 20). The purpose of these battle stories was never to tell the reader to commit violence in God’s name. Rather, they show God bringing his justice on human evil and delivering Israel from being annihilated by the Canaanites.

Joshua 13-24: Dividing the Land and a Call to Faithfulness

Now, back to the book’s design. After years of battles, an aging Joshua divides up the land for the 12 tribes (Josh. 13-22). Most of this section is made up of lists of boundary lines. And let’s be honest here, it’s kind of boring and hard to visualize. It’s like reading a map with no pictures! For the Israelites, however, these lists were super important. This was the fulfillment of God’s ancient promise to Abraham that his descendants would inherit the land (Gen. 12:6-7). It was finally all coming to pass, down to the last detail.

This all leads to the final section found in chapters 23-24. Joshua gives two final speeches to the people—very similar to Moses’ final speeches in Deuteronomy. Joshua reminds them of God’s generosity in bringing them into the land and rescuing them from the Canaanites. He calls them to turn away from Canaanite gods and to be faithful to the covenant that they made with God. If they do so, it will lead to life and blessing in the land. But if they’re unfaithful, Israel will call down on itself the same divine judgment the Canaanites experienced, and they’ll be kicked off the land back into exile.

The book concludes with Joshua leaving Israel with a choice. What are they going to do? That’s the big question that looms as the book of Joshua comes to a close.

Frequently Asked Questions

Here are some of the most common questions people ask online about this book.

The biblical portrait of Canaan is complex. The land of Canaan is described as a place “flowing with milk and honey” (Exod. 3:8; Exod. 3:17), an image of abundance that recalls the abundance of Eden’s garden (Gen. 2). God promises to give this fruitful land to Abraham and his descendants (Gen 15:18).

But when the Israelites enter the land, it’s occupied by several Canaanite nations who engage in practices that oppose the way of God—including child sacrifice (Deut. 12:31). According to Leviticus 18:24-25, this kind of behavior defiles the land, so it vomits out the Canaanites. But God has patience with them, waiting for centuries until their wrongdoing is “complete” before bringing judgment (Gen. 15:16).

God also warns the Israelites to never follow in the Canaanites’ footsteps, or they’ll risk the land vomiting them out too (Lev. 18:26-28)! And ultimately, that happens when the Israelites are sent into Babylonian exile. So while Canaan can symbolize abundance as God’s promised land, the Canaanites can symbolize those who live in opposition to God’s ways. And even God’s own people can act like Canaanites, leading them to face the same destructive consequences the Canaanites experienced.

However, the Hebrew Bible also portrays some Canaanites positively. Abraham has good relationships with his Canaanite neighbors, and a few Canaanite allies even risk their own lives to help him rescue his nephew Lot from invading kings (Gen. 14:13-16; Gen. 14:24). Also, Rahab of Jericho (Josh. 2) and Caleb the Kenizzite (Num. 32:12; see Gen. 15:18-19) align themselves with the people of Israel and their God, and as a result, they end up receiving God’s blessing.

The Bible never explicitly tells us why God chooses Canaan as the land promised to Abraham’s descendants. But it forms a land bridge between major world powers, providing an ideal location for the Israelites to fulfill their calling to be a “light to the nations” (Isa. 42:6; see also Isa. 60:1-3).

It is also described as a land “flowing with milk and honey” (Exod. 3:8; Exod. 3:17), a fruitful place where God will lavishly provide for the Israelites. But unlike Egypt, whose fertility comes from the annual flooding of the Nile, Canaan needs rain to grow crops. This makes it more susceptible to famine (see Gen. 12:10; Gen. 26:1; Ruth 1:1; 2 Sam. 21:1). So the Israelites must depend on God to bring rain, which God promises will happen if they follow him (Lev. 26:3–5).

God’s choice to give the land of Canaan to the Israelites does not mean God is granting permission for the people to do whatever they want with it—quite the opposite. God continually reminds the Israelites that they live as “foreigners” and “sojourners” on the land (Lev. 25:23). They are not to defile the land (Lev. 18:24-30), but to allow it to rest every seventh year (Lev. 25:1-7). So for Israel, Canaan is both a gift and a responsibility to faithfully care for God’s land.

Exodus 23:28-30 states that God will not drive out all the people who live in Canaan at once. But why not? Because doing so would make the land desolate and cause the wild animals to increase and become a threat to the Israelites. Instead, it’s a slow process of driving out the Canaanites. And because Israel will live in proximity to the Canaanites for many years, God warns them to not make the mistake of forming covenants with the Canaanites or their gods (Exod. 23:32-33).

But the Israelites violate their relationship and agreement with God; they abandon God and worship the gods of their Canaanite neighbors. So God says he will no longer drive out the powerful nations who are still left in the land (Judges 2:1-3; Judges 2:20-21).

Those who are not driven out will remain for the purpose of testing whether the Israelites will choose to follow God or walk in the ways of the Canaanites (Judges 2:22-23).

We learn in the book of Judges (directly after Joshua) that over and again, the Israelites choose to adopt the ways of the Canaanites. In doing so, they forfeit the blessing of God’s protection.

According to the Hebrew Bible, God brings judgment upon Canaanite cities because the people who live there engage in abominable practices that defile the land (Lev. 18:24-25; Deut. 12:29-31). But when the Israelites encounter their first Canaanite city, Jericho, they don’t immediately attack it. Instead, at God’s instruction, they march around the city for six days. Then, on the seventh day, they circle the city seven times, shouting loudly. And while they march and shout, God causes the city’s walls to collapse (Josh. 6:1-20).

Before the Israelites begin their seven-day march around the city, Joshua sends two spies into the city. Jericho’s king comes looking for them, but a Canaanite prostitute named Rahab hides the spies and helps them escape (Josh. 2). She’s heard about what Yahweh has done for Israel, and she aligns herself with the Israelites and their God. And as a result, she and her family are spared (Josh. 6:22-25).

Now what’s the point of this strange battle plan to march around the city for seven days? In part, it gives the people of Jericho time to respond similarly to Rahab and turn to Yahweh. It also makes it clear to Israel that this is God’s battle. This war will not be won by Israel’s strength, and it is not for their enrichment either. They’re even instructed to devote the wealth of Jericho to God (Josh. 6:18-19). But when an Israelite named Achan snatches some of the plunder for himself, he aligns himself with the Canaanites and, therefore, is treated as a Canaanite (Josh. 7).

So the story of Jericho shows that the book of Joshua is about more than a battle between Israelites and Canaanites. All who turn to Yahweh and follow his ways, whether Israelite or Canaanite, receive his blessings. But those who turn away from him, whether Israelite or Canaanite, face the consequences of their choice.

When the Israelites enter the promised land, God leads them into battle against the Canaanites who already live there. God could have overcome Israel’s enemies without requiring the people to fight, as when he sent plagues on Egypt to rescue them from slavery. But here God instructs them to face their enemies in battle and to trust him with the outcome (Deut. 20:1).

The Bible doesn’t tell us why God calls the Israelites to fight, but the book of Joshua undermines some common ancient assumptions about warfare. Israel does not fight like the other nations. Their success in battle comes from God, rather than their own military strength (Josh. 6; Ps. 44:3).

And God promises to give the Israelites victory—even as they face nations much stronger than themselves—if they follow his instructions (Deut. 9:1-3; Deut. 11:22-25). When they don’t listen to him, God does not fight for them. For example, God commands the Israelites to not take any plunder when they defeat the city of Jericho. So when a man named Achan hides some of it in his tent, Israel is defeated in their battle against Ai (Josh. 7). But after the people address the problem of the stolen goods, God leads them to victory over Ai (Josh. 8).

God makes it clear to Israel that he is not on their side. Rather, God invites the Israelites to align themselves with him (Josh. 5:13-14). So Israel’s fight against the inhabitants of the promised land becomes an opportunity to trust God and follow his ways.

When God instructs Moses to appoint Joshua as Israel’s leader, he describes him as “a man in whom is the Spirit” (Num. 27:18). Joshua demonstrates his Spirit-filled character early on as Moses’ helper. Exodus 33 describes Moses speaking face-to-face with God in the tent of meeting and then returning to Israel’s camp—with Joshua staying behind in the tent (Exod. 33:11). Even in his youth, Joshua was hungry for the presence of God.

Later, Joshua is one of only two spies sent into Canaan who brings back a good report, while the other spy reports create fear and distrust. Joshua trusts that God will protect Israel as they enter the promised land (Num. 13:1-14:10).

When Joshua becomes Israel’s leader after Moses’ death, God calls him to courageously follow his instructions (Josh. 1:7). And Joshua does so, even when God’s instructions don’t make sense from a human perspective. As the Israelites enter Canaan, God tells Joshua that his battle plan against Jericho is to lead the people to march around the city seven times. Joshua obeys, and the city falls (Josh. 6:1-21).

But Joshua makes big mistakes too. When an enemy nation sends an envoy in disguise to make a treaty with Israel, Joshua falls for the trick because he does not ask God for wisdom before accepting their offer (Josh. 9:14-15).

Though imperfect, Joshua consistently works to follow God and calls Israel to do the same. Before his death, Joshua leads the Israelites to renew their covenant with God, making a commitment of his own: “As for me and my house, we will serve Yahweh” (Josh. 24:15, BP Translation).

When the Israelites fight against the Amorites, Joshua prays for the sun to stand still, and God listens to his prayer (Josh. 10:1-14). While this story is full of puzzles and ambiguities, it highlights the extraordinary help God sometimes gives people.

The Bible doesn’t tell us why Joshua makes this request. Perhaps he’s asking for more daylight hours so that his troops don’t have to fight in the dark, though this seems unnecessary because the battle begins at daybreak (Josh. 10:9). Another possibility is that he’s asking for an eclipse or some other form of omen in the sky, which would encourage his troops or terrify his enemies.

Although the reasoning behind Joshua’s request remains unclear, the effect of God’s response is undeniable. As Joshua goes to battle with the Amorites, God tells him not to be afraid and promises, “I have given them into your hand; not one of them will stand (‘amad) before you” (Josh. 10:8, BP Translation). God’s promise is real, the Amorites cannot withstand Israel in battle, and this point is emphasized when the sun and moon both “stand” (‘amad) in answer to Joshua’s prayer (Josh. 10:13).

This story also recalls details from Israel’s earlier victories, in order to show that God is the one who fights Israel’s battles for them—God alone grants them success. God sends hailstones upon the Amorites (Josh. 10:11), just as hailstones fell on Egypt during the plagues (Exod. 9:18-35). And the sun “stands” (‘amad) just like the waters of the Jordan “stood” (‘amad) to let the Israelites pass through as they entered Canaan (Josh. 3:16). In their victory against the Amorites, God demonstrates that he will intervene in powerful ways when Israel is willing to trust him for deliverance.