BibleProject Guides

Guide to the Book of Joshua

About

Before looking at the book of Joshua, let’s back up and remember the story of the Bible so far. God chose Abraham to bring his blessing to the nations. Abraham’s family grew and became the people of Israel, and after some time, they were enslaved in Egypt. Through Moses, God rescued the Israelites and brought them out of Egypt to Mount Sinai where he made a covenant with them. Then, God brought the people through the wilderness despite the hardships and rebellions along the way. Finally, as Israel camped outside the promised land, Moses called upon them to obey God’s commandments, so that they could show the other nations the true character of God. The book of Joshua picks up shortly after Moses dies as Israel prepares to enter the land.

The storyline of Joshua is designed with four main movements. Joshua leads Israel into the promised land (Josh. 1-5). Once they’re there, they are met with hostility from the native Canaanites, and they engage in battle (Josh. 6-12). After their victories, Joshua divides up the land as an inheritance for the twelve tribes (Josh. 13-22), and finally, the book concludes with Joshua delivering his final words to the people (Josh. 23-24).

Joshua 1-5: Israel Enters the Promised Land

Chapter 1 begins with Moses’ death and the appointment of Joshua as the new leader of Israel. The author intentionally presents Joshua as a new Moses. Like his predecessor, Joshua calls on the people to obey the terms of the covenant given to Israel at Mount Sinai that are found in the Torah. In chapter 2, Joshua sends spies into the land, just as Moses had in Numbers 13-14. Things go much better this time, and even some Canaanites, such as Rahab the prostitute, turn to follow the God of Israel. Joshua then leads all of Israel across the Jordan River and into the land. Just as the sea parted for Moses in Exodus, so here the river parts as priests carrying the ark of the covenant lead the Israelites across to the land.

The story transitions in chapter 5 as the Israelites look back to their roots as God’s covenant people. They have the new generation circumcised to honor that covenant, and they celebrate their first Passover in the new land. Just as they prepare to go forward, Joshua has an encounter with a mysterious warrior who, it turns out, is the angelic commander of God’s army. Joshua asks, “Are you for us or for our enemies?” The warrior responds, “Neither,” which shows that the real question is whether Joshua is on God’s side. Chapter 5 makes clear that this story will not be about the Israelites versus the Canaanites. Rather, it is God’s battle. Israel will play the role of spectators and only sometimes act as supporters in his purposes.

Context

The events described in Joshua take place in the ancient Near East, including the land of Canaan and city of Jericho, after the death of Moses.

Literary Styles

Joshua contains mostly narrative, with some poetry and discourse woven throughout.

Who Wrote the Book of Joshua?

Many Jewish and Christian traditions hold that Joshua is the primary author. However, authorship is not explicitly stated within the book.

Key Themes

- Israel’s need to trust God for entry into the promised land

- God’s command for Israel to pursue peace with other nations

- God’s eradication of human evil and upholding of justice

- The generosity of God for protection and rescue

Structure

The structure of Joshua is divided into three parts. Chapters 1-5 show Israel preparing to enter the land, 6-12 contain stories of battle, and 13-24 establish the tribal boundaries, as well as Joshua’s encouragement to be faithful to God.

Joshua 6-12: Victorious Battles Over the Canaanites

This leads into the next section of the book of Joshua, in which we find stories about all the conflicts Israel had with different Canaanite groups as they entered the land. Chapters 6-8 retell the story of two battles in detail, followed by chapters 9-12, which are a series of short stories that condense years of battles into a few brief summaries.

The first two battles against Jericho and Ai offer contrasting portraits of God’s faithfulness and Israel’s failure. At Jericho, Israel is to take a completely passive approach, letting God’s presence in the ark lead them around the city with music for six days. Just as Rahab turned to the God of Israel, perhaps the people of Jericho will do the same. They do not, sadly, and so on the seventh day when the priests blow their trumpets, the walls miraculously crumble and Israel is led to victory. The point of this story is that God is the one who will deliver his people. Israel simply needs to trust and wait.

The battle at Ai makes a contrasting point, showing what happens if Israel doesn’t trust their God. An Israelite named Achan stole goods from Jericho that were meant to be devoted and offered to God. Then he proceeded to lie about it—a pretty selfish move after all that God had done for Israel. So when Israel enters the battle of Ai, they are defeated. It’s only after humble repentance and severely dealing with Achan’s sin that they gain victory over Ai.

Together, these two stories are placed at the front of the battle narratives to make an important point. To inherit the land, Israel has to be obedient and trust in God’s commands. This isn’t their battle, and God isn’t their trophy.

The second part of this section begins in chapter 9 as the Gibeonites, a Canaanite people group, do what Rahab did—turn to follow Israel’s God and make peace. This is in stark contrast to many other Canaanite kings, who form coalitions to destroy Israel. Israel, however, wins all of these battles by a landslide. The section concludes with a summary list of all the victories won by Moses and Joshua (Josh. 12).

Now, let’s stop for a moment because odds are that these stories and the violence described in the battles are going to bother you. If you’re a follower of Jesus, you’re bound to wonder, “Didn’t Jesus say, ‘love your enemies’? Why is God declaring war?”

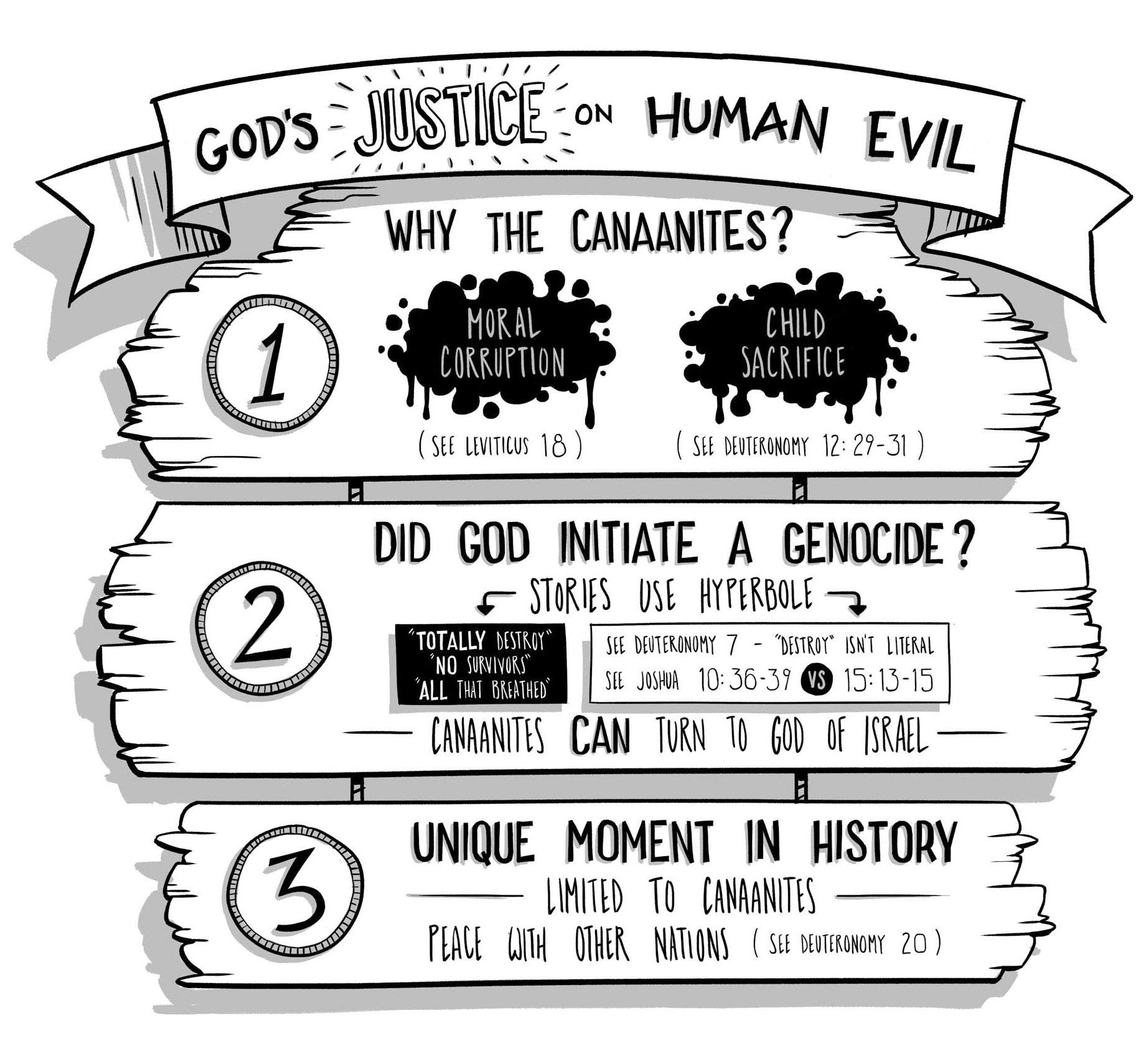

First of all, why the Canaanites? The main reasons given are that their culture had become morally corrupt, especially when it came to sex (Lev. 18), and because they widely practiced child sacrifice (Deut. 12:29-31). God didn’t want these practices to influence Israel, so these groups needed to be expelled.

But that only raises the second question, “Did God really command the destruction of all the Canaanites, like a genocide?” At first glance, we see the phrases “totally destroy” and “leave no survivor” or “anything that breathes.” However, when we look more closely, we discover that these phrases are used by the author as hyperbole and are not meant literally.

Look again at God’s original command in Deuteronomy 7. Israel is first told to “drive out” the Canaanites as well as to “totally destroy” them. This is immediately followed by commands to not intermarry or enter business deals with them. You can’t marry or do business with people that you’ve literally destroyed! Moses is using hyperbole, an exaggerated expression, to make his point with force.

The same idea applies to the stories told in Joshua. For example, we’re told in Joshua 10:36-39 that Israel left “no survivors'' in either Hebron or Debir, but later in 15:13-15, these towns are still populated by Canaanites. In this way, the stories of Joshua fit in with other ancient battle accounts in their use of nonliteral hyperbole as part of the narrative style.

So the word “genocide” doesn’t really fit with what we see here, especially in light of the stories about Canaanites who did turn to the God of Israel, like Rahab or the Gibeonites. God was very open to all who would turn to him in repentance and trust.

As a last thought, these stories mark a unique moment in history. These battles were limited to the handful of people groups living in the land called Canaan. We know this was a temporary and limited measure because Israel was commanded by God to pursue peace with all other nations (Deut. 20). The purpose of these battle stories was never to tell the reader to commit violence in God’s name. Rather, they show God bringing his justice on human evil and delivering Israel from being annihilated by the Canaanites.

Joshua 13-24: Dividing the Land and a Call to Faithfulness

Now, back to the book’s design. After years of battles, an aging Joshua divides up the land for the 12 tribes (Josh. 13-22). Most of this section is made up of lists of boundary lines. And let’s be honest here, it’s kind of boring and hard to visualize. It’s like reading a map with no pictures! For the Israelites, however, these lists were super important. This was the fulfillment of God’s ancient promise to Abraham that his descendants would inherit the land (Gen. 12:6-7). It was finally all coming to pass, down to the last detail.

This all leads to the final section found in chapters 23-24. Joshua gives two final speeches to the people—very similar to Moses’ final speeches in Deuteronomy. Joshua reminds them of God’s generosity in bringing them into the land and rescuing them from the Canaanites. He calls them to turn away from Canaanite gods and to be faithful to the covenant that they made with God. If they do so, it will lead to life and blessing in the land. But if they’re unfaithful, Israel will call down on itself the same divine judgment the Canaanites experienced, and they’ll be kicked off the land back into exile.

The book concludes with Joshua leaving Israel with a choice. What are they going to do? That’s the big question that looms as the book of Joshua comes to a close.

Israel enters the land of Canaan, fulfilling God’s promise to Abraham, and Joshua instructs Israel to live according to the covenant.